Point Mutation Cell Line Generation: 4 Core Methods & Applications

With the rapid advances in genome editing technologies, the generation of point mutation cell lines has become an indispensable tool in modern life sciences research. From dissecting the molecular mechanisms of single-nucleotide variants to modeling disease-associated mutations, facilitating targeted drug development, and enabling gene therapy translation, this technology spans the full spectrum from basic research to clinical applications.In this article, we break down the key applications of point-mutant cell lines, and provide an in-depth analysis of four commonly used generation strategies, detailing their underlying principles, practical considerations, and optimal use cases, to help researchers quickly select the most suitable experimental approach.

Understanding the Applications of Point Mutation Cell Lines

their ability to precisely model specific genetic variants, point mutation cell lines play an irreplaceable role across multiple research areas:

1.Basic Research: A “Precision Tool” for Decoding Gene Function

Point mutation cell lines allow researchers to accurately introduce specific nucleotide changes and observe their molecular and phenotypic consequences. This capability is critical for elucidating gene function, regulatory mechanisms, and variant-specific effects.

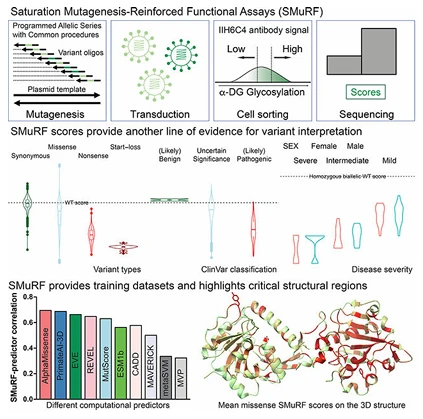

For example, a study published in Cell utilized a saturation mutagenesis-assisted functional approach (SMuRF) to systematically evaluate all possible single-nucleotide variants in the FKRP and LARGE1 genes, which are associated with α-dystroglycanopathies. The functional scores obtained correlated strongly with clinical genetic variant databases and reflected disease severity, providing an efficient method to study the functional impact of rare pathogenic mutations.

Figure 1. Functional analysis of genes associated with rare diseases

2.Disease Research: “Cellular Models” for Recapitulating Pathological States

Many monogenic diseases, cancers, and other disorders are closely associated with specific point mutations. Point-mutant cell lines can faithfully replicate the pathological cellular state corresponding to these mutations. For example: Cells carrying CFTR point mutations provide a direct readout of the mutation's effect on protein function, such as misfolding or impaired trafficking.Point mutations in oncogenes like PIK3CA or K-RAS can serve as cancer-relevant markers, offering stable platforms for studying disease mechanisms, early diagnostic biomarkers, and therapeutic interventions.

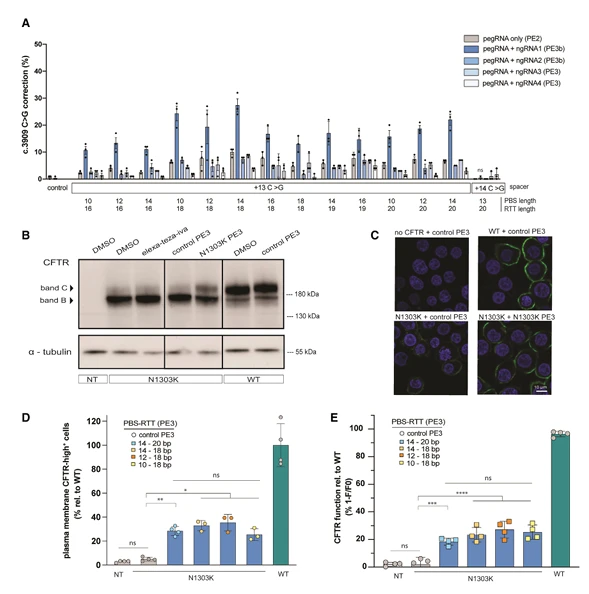

For instance, a study targeting CFTR L227R and N1303K mutations employed precise genome editing to correct these mutations in HEK293T and 16HBE cell lines, as well as patient-derived rectal organoids. Following correction, the glycosylation, subcellular localization, and ion channel function of CFTR were fully restored, providing critical insights for cystic fibrosis pathology and functional studies.

Figure 2. Characterization of pathogenic CFTR point mutations in cystic fibrosis

3.Drug Development: An “Efficient Platform” for Target Screening and Validation

Point-mutant cell lines provide a rapid and reliable platform to validate drug targets. By generating cells with specific point mutations, researchers can:① Screen for small-molecule inhibitors with high specificity toward the mutated target.② Model patient-derived resistance mutations to assess drug efficacy in a clinically relevant context.

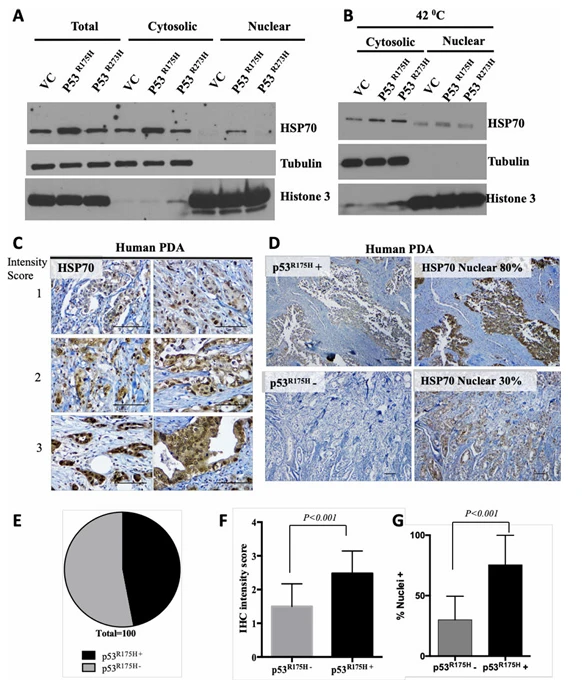

For example, a study investigated the TP53 R175H mutation, a common drug-resistance-associated variant in pancreatic cancer. Using immortalized pancreatic ductal epithelial cells harboring KRAS mutations, the researchers introduced the TP53 R175H variant via a lentiviral system to replicate the resistance-associated mutation observed in patients.Subsequent drug testing revealed that the mutant TP53 protein induced HSP70 expression and binding, sustaining oncogenic signaling and promoting cancer cell proliferation. Targeted drug interventions against HSP70 and related pathways successfully reduced the proliferation of the mutant cells, providing novel therapeutic targets and experimental validation for overcoming resistance in pancreatic cancer.

Figure 3. Mutant p53 R175H promotes nuclear accumulation and stabilization of HSP70

4.Gene Therapy: A “Critical Support” for Clinical Translation

Many genetic diseases are caused by point mutations, and point-mutant cell lines serve as both validation models for gene therapy and therapeutically relevant cellular material.

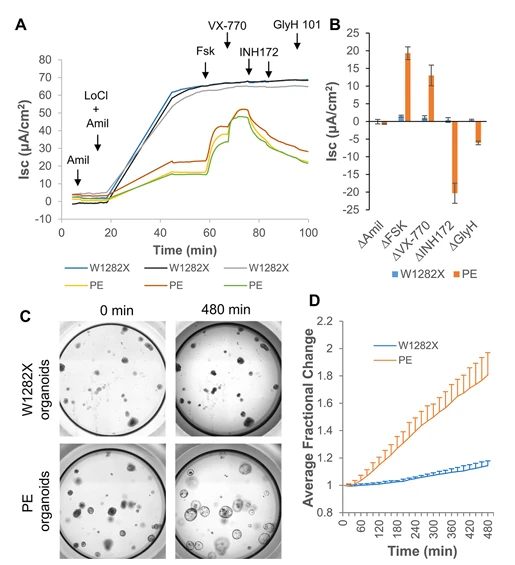

For example, using precise genome editing technologies, researchers can correct CFTR point mutations in cells derived from cystic fibrosis patients, restoring normal protein function. Corrected induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can then be differentiated into disease-relevant cell types, providing a platform to assess the efficacy and safety of therapeutic interventions. These studies offer critical experimental support for the clinical translation of gene therapy.

Figure 4. Correction of nonsense mutations in CFTR for cystic fibrosis

Four Common Strategies for Generating Point Mutation Cell Lines

Based on years of hands-on experience in genome editing, we have systematically summarized four core strategies for constructing point-mutant cell lines. Each method is analyzed in terms of underlying principle, key experimental steps, and major advantages, followed by a comparison of their optimal application scenarios. This helps researchers select the most appropriate approach and efficiently generate precise point mutations.

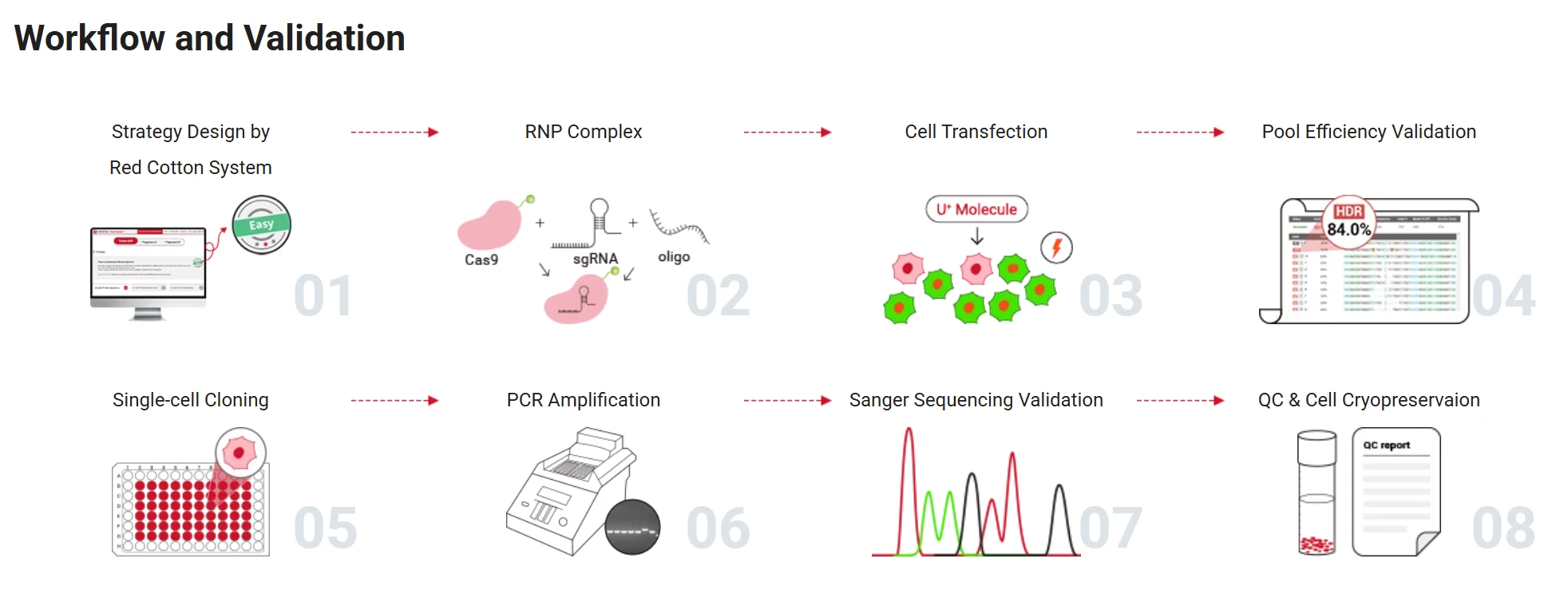

1. RNP (Ribonucleoprotein) Method

For those seeking a simple, cost-effective, and flexible workflow, the RNP method is highly recommended.

Principle

RNP stands for RNA-Protein Complex, which consists of sgRNA (single-guide RNA) that directs Cas9 to the target site and the Cas9 nuclease itself. The complex is pre-assembled in vitro and then delivered directly into cells. Think of it as providing the cell with a “precision molecular scissors”: once the complex locates the target DNA, Cas9 generates a double-strand break, and the pre-designed repair template containing the desired point mutation is used to guide homology-directed repair (HDR), resulting in a precise nucleotide change.

Key Steps for the RNP Method

- Prepare sgRNA, Cas9 protein, and repair template: ①Design the sgRNA (we recommend using Ubigene's Red Cotton™ CRISPR system ) .②Mix the sgRNA with Cas9 protein in the appropriate ratio and incubate at room temperature to form a stable RNP complex.③Simultaneously, prepare the repair template (ssODN or dsDNA) containing the desired point mutation.

- Deliver the editing components into cells: Introduce the RNP complex and repair template into cells using electroporation or lipid-based transfection.

- Isolate successfully edited cells: ① If the repair template carries a fluorescent tag, use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich for positive cells.② Dilute and plate the enriched cells into 96-well plates for clonal expansion to obtain single-cell-derived clones.

- Validate the edit: Extract genomic DNA from each clone and perform PCR and sequencing to confirm that the desired point mutation has been correctly integrated.

Advantages of the RNP Method

- Minimal risk of exogenous DNA integration and relatively low off-target effects.

- Rapid action: Cas9 protein is immediately active upon delivery, bypassing the need for transcription and translation, resulting in a shorter experimental cycle.

- Flexible and cost-effective sgRNA design, allowing easy adaptation to different target sites.

Figure 5. Point Mutation Cell Line Generation Workflow

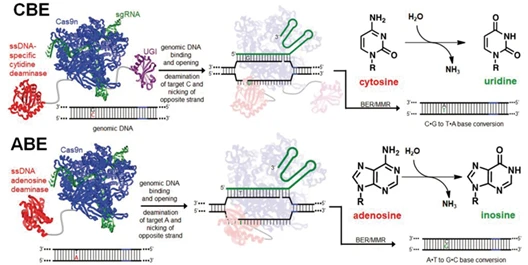

2.Base Editing

If your experimental goal is precise single-nucleotide conversion—for example, C→T or A→G—and you want to avoid risks associated with double-strand DNA breaks (such as apoptosis or random insertions/deletions), a base editor is a tailor-made tool.

Principle

A base editor is a modified CRISPR tool: Cas9 is converted into a nickase that cuts only one DNA strand, and fused with a deaminase enzyme that catalyzes the desired base change. Guided by sgRNA, the editor locates the target base, and the deaminase directly converts it to the desired nucleotide. This process bypasses double-strand breaks, achieving high precision and minimal cellular stress.

Key Steps

- Select the appropriate editor and design sgRNA:① For C→T conversions, use a cytosine base editor (CBE).② For A→G conversions, use an adenine base editor (ABE).③ Design the sgRNA to position the target nucleotide within the editor's active editing window.

- Transfection and enrichmen: Deliver the base editor construct and sgRNA into cells (no repair template required).Enrich for successfully edited cells using fluorescent markers or selectable resistance genes.

- Clonal isolation and validation: Expand single-cell clones and confirm precise nucleotide conversion by sequencing.

Advantages of Base Editing

- No double-strand DNA breaks, making it highly compatible with sensitive cells such as stem cells and neurons.

- High editing efficiency: single-nucleotide conversions are often more successful than traditional HDR-based approaches.

- No repair template required, simplifying the workflow and making it particularly suitable for modeling disease-relevant single-nucleotide variants (SNVs).

Figure 6. Schematic of cytosine and adenine base editors (CBE and ABE)

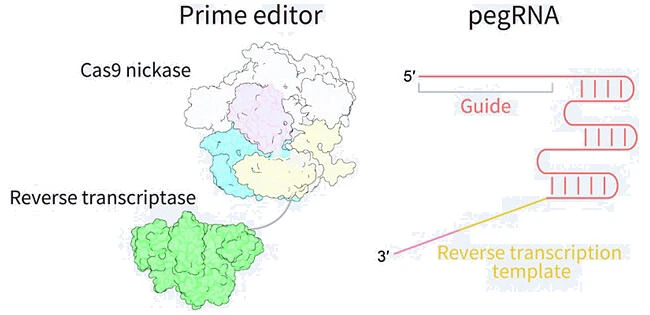

3.Prime Editing

For more complex editing needs — such as not only single-base changes but also small insertions (≤40 bp) or deletions (≤80 bp)—the prime editor is currently the most versatile tool, often described as the “knife” of genome editing.

Principle

The prime editor is a fusion of Cas9 nickase and reverse transcriptase, guided by a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The pegRNA both directs the complex to the target site and carries a reverse transcription template containing the desired mutation or small insertion/deletion. Upon target recognition, Cas9 nicks one DNA strand, and the reverse transcriptase synthesizes the edited sequence directly into the genome, without introducing double-strand breaks or requiring an external repair template.

Key Steps:

- Design pegRNA and optional nicking sgRNA: The pegRNA includes a guide sequence to locate the target site and a reverse transcription template encoding the desired edit.For the PE3 system (higher efficiency), design an additional sgRNA to nick the opposite strand and facilitate editing.

- Transfection into cells: Deliver the prime editing constructs into cells, typically via plasmid transfection (electroporation or lipid-based delivery).

- Enrichment and validation: Enrichment and validation

Advantages of Prime Editing

- Highly versatile editing: capable of single-base substitutions, small insertions, and small deletions.

- Extremely high precision, with low off-target effects.

- Broad applicability, making it a popular tool for gene therapy research.

Figure 7. Core components and mechanism of the prime editor

4.Antibiotics-based Knock-in Method

For complex or hard-to-target mutation sites where RNP or base editing cannot easily design a functional gRNA, the plasmid-based antibiotic selection method is recommended.

Principle

gRNA/Cas9-expressing plasmids and a donor plasmid containing homology arms and a selectable resistance cassette to achieve homology-directed repair (HDR) and introduce the desired point mutation. The resistance gene is typically embedded within an intron and flanked by LoxP sites, allowing Cre-mediated removal after selection. Antibiotic screening significantly increases the likelihood of isolating correctly edited clones.

Key Steps

- Construct the plasmid: Design gRNA within a target gene intron.Prepare left and right homology arms (typically 600–1000 bp) and a donor plasmid carrying the desired mutation and resistance cassette.

- Cell transfection: Deliver the gRNA/Cas9 plasmid along with the donor plasmid into cells using lipid-based transfection.

- Antibiotic selection: Select for positive clones using the appropriate antibiotic.Transfect Cre-expressing plasmid to remove the resistance cassette if desired.

- Single-cell cloning and validation: Dilute surviving cells into 96-well plates for clonal expansion.Screen clones using PCR and sequencing to confirm successful point mutation integration.

Advantages of Antibiotics-based Knock-in Method

- High screening efficiency, suitable for cells with low HDR activity.

- Flexible gRNA design, not limited by proximal PAM sites.

- Can generate complex or low-frequency point mutation models that are challenging for RNP or base editing.

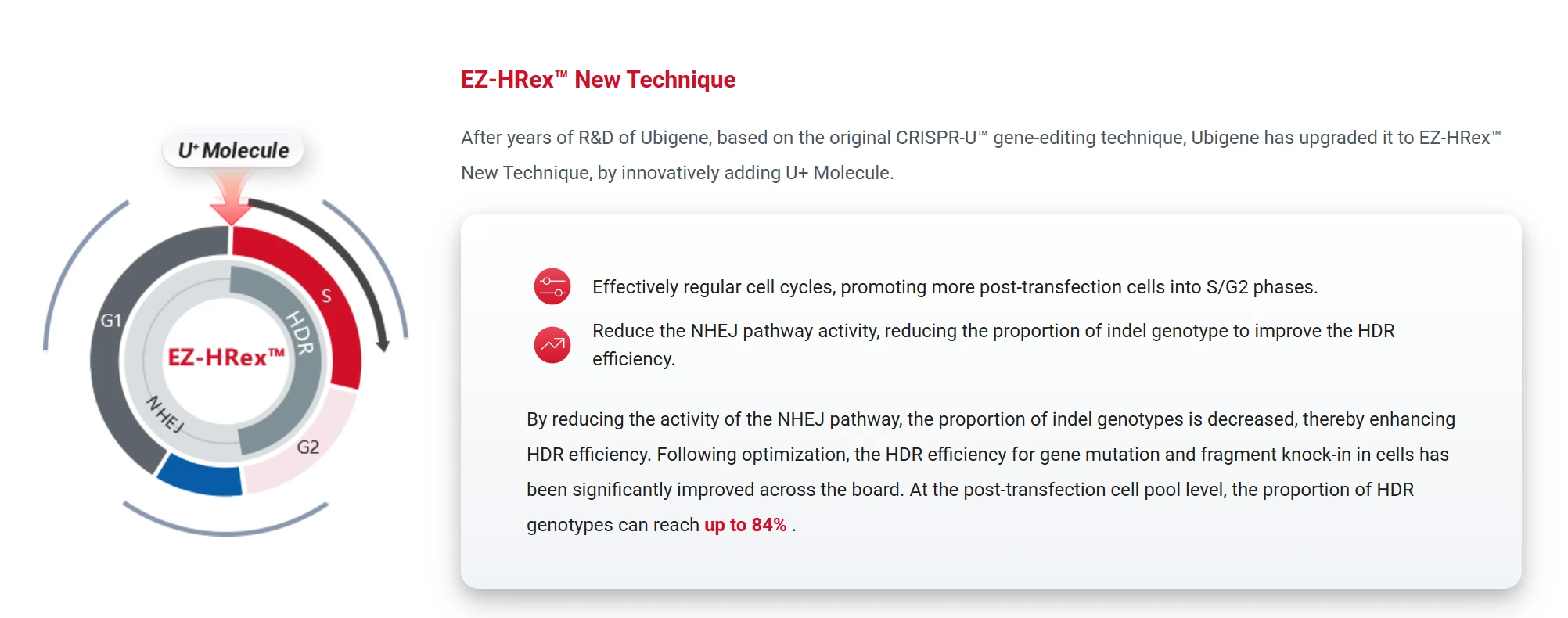

Ubigene Technical Support: EZ-HRex™ Technology

Ubigene's EZ-HRex™ represents an upgraded HDR enhancement platform that introduces the U+ small molecule, broadly applicable for point mutations and small fragment knock-in models.

Key features

- Cell cycle modulation: increases the proportion of cells in S/G2 phase post-transfection, enhancing HDR efficiency.

- NHEJ pathway inhibition: significantly improves HDR efficiency up to 84%.

- Universal compatibility: supports all four point mutation generation strategies (RNP, Base Editing, Prime Editing, and Antibiotics-based PM).

- Scalable applications: ideal for large-scale mutation modeling, drug screening, and functional validation platforms.

How to Choose Among the Four Strategies?

| Method | Key Advantages | Suitable Editing Types | Recommended Applications |

| RNP Method | Low off-target risk, no exogenous DNA integration | Standard point mutations (e.g., SNPs) | Most adherent cells, general point mutations |

| Base Editing | No double-strand breaks, high efficiency | Standard point mutations (e.g., SNPs) | Single-base substitutions, sensitive cells, SNV modeling |

| Prime Editing | Highly versatile and precise | Mutations not covered by base editors (e.g., small insertions/deletions) | Complex mutations, gene therapy research |

| Antibiotics-based Knock-in | Works in low HDR background cells | Targets lacking suitable gRNA or with low editing efficiency | Complex or low-frequency point mutation models |

In reality, there is no single “best” method for generating point mutation cell lines, only the approach that is most suitable for your specific experimental goals. If you are creating a point mutation cell line for the first time, it is recommended to review all available strategies and choose the one that best matches your cell type, mutation complexity, and research objectives. Should you encounter practical challenges—such as low transfection efficiency or difficulty obtaining homozygous clones, feel Free to contact us for expert technical support.