CRISPR Library Screening in Drug Discovery: Applications and Emerging Trends

Challenges in Drug Discovery

Globally, the development of novel therapeutics faces long timelines, high costs, and overall low success rates. Statistical analyses indicate that the development of an innovative drug, from early-stage research to market approval, typically requires 6-10 years or longer, with substantial and sustained financial investment. Despite these efforts, only a small fraction of candidate compounds ultimately reach the market.

In the early stages of drug discovery, the identification and functional validation of disease-relevant targets are particularly critical, and also among the most resource- and time-intensive steps. The biological relevance and druggability of a target directly influence the likelihood of success in downstream drug design and clinical development. Traditional target discovery approaches often rely on low-throughput experiments or hypothesis-driven strategies, which may limit the systematic elucidation of gene function and the causal relationships between genes and disease phenotypes. Consequently, the efficiency and scope of target screening are constrained.

Against this backdrop, there is a growing demand for high-throughput, systematic technologies that can accelerate target identification and validation, providing more robust and scalable strategies to support early-stage drug discovery.

Technical Value of CRISPR Library Screening

CRISPR library screening is a high-throughput functional genomics approach based on the CRISPR/Cas gene editing system, enabling systematic perturbation and functional assessment of large numbers of genes within a single experiment. Typically, this approach involves the construction of pooled single-guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries containing tens of thousands of sequences targeting either the whole genome or specific gene subsets. These libraries are introduced into a population of cells, allowing parallel analysis of the phenotypic effects of multiple gene perturbations under the same experimental conditions.

During the screening process, the cell population is exposed to defined selective pressures or experimental conditions—such as drug treatment, environmental stress, or functional phenotype assays—resulting in differential proliferation, survival, or functional behaviors among cells harboring distinct sgRNAs. High-throughput sequencing is then used to quantitatively compare the abundance of each sgRNA before and after selection, enabling the identification of genes that exert significant effects on cellular phenotypes under specific conditions and facilitating the inference of their functional roles in biological processes or disease models.

Compared with approaches that rely primarily on correlating molecular signatures or phenotypic profiles, CRISPR library screening directly perturbs gene function, establishing a clear causal relationship between genetic perturbation and phenotypic outcome. This capability provides high-throughput, systematic support for early-stage target discovery, functional gene identification, and mechanistic studies, making CRISPR screening a powerful tool for drug target identification and validation.

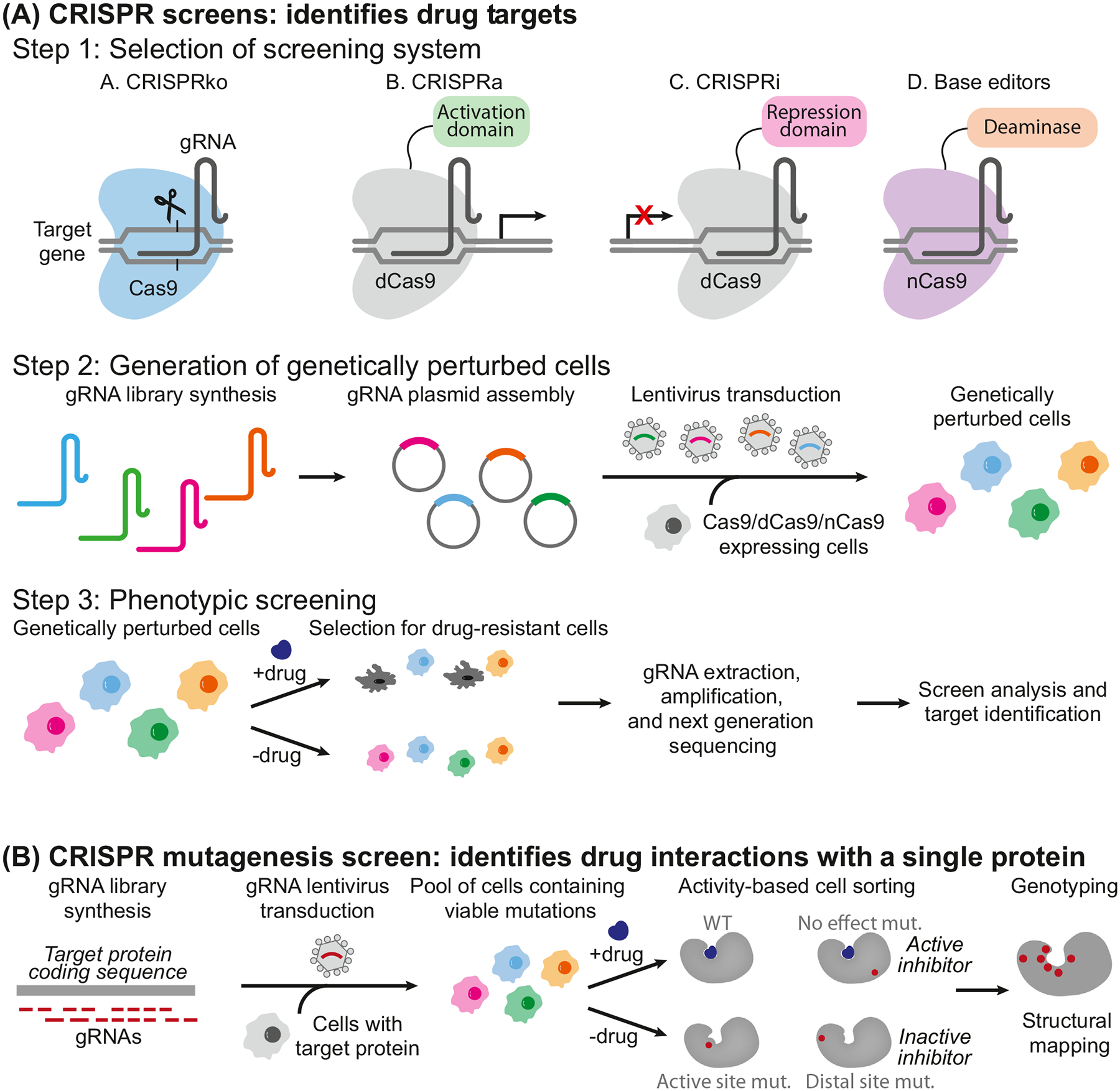

Figure 1. Schematic Workflow of Genome-wide CRISPR Screening

A genome-wide sgRNA library is constructed and delivered into cells via transfection or infection. The cell population is then subjected to selective pressure, such as drug treatment or other functional assays. High-throughput sequencing is used to quantify changes in sgRNA abundance before and after selection, enabling the identification of genes that play critical roles in the observed phenotype.

Fundamental Principles of CRISPR Library Screening

CRISPR screening is based on the CRISPR-Cas gene editing system, enabling programmable, large-scale perturbation of target genes combined with phenotypic selection and sequencing analysis to achieve systematic functional characterization. Depending on the type of Cas protein and regulatory design, CRISPR screening can be classified into three main application modes:

1.CRISPR-KO (Knockout)

CRISPR-KO screening typically employs a nuclease-active Cas9 protein guided by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) to induce double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic loci. These DSBs are primarily repaired via the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which frequently introduces insertions or deletions (indels) that shift the reading frame and result in loss of gene function. CRISPR-KO is suitable for systematically investigating the effects of complete gene loss on cellular phenotypes, biological processes, or disease models, and remains one of the most widely used screening strategies.

2.CRISPRi (CRISPR Interference, Transcriptional Repression)

CRISPRi screening utilizes a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a transcriptional repressor domain, such as KRAB. The complex is guided by sgRNAs to bind promoter or transcription start regions of target genes, physically blocking transcriptional machinery and recruiting repressive chromatin modifiers to effectively silence gene expression. Because CRISPRi does not alter the underlying DNA sequence, it enables stable but reversible downregulation of gene expression, making it particularly suitable for studying essential genes, dosage-sensitive genes, or cases where fine-tuned expression modulation is required.

3.CRISPRa (CRISPR Activation, Transcriptional Activation)

CRISPRa also uses the dCas9 system but is fused to transcriptional activator domains (e.g., VP64, p65, Rta). Guided by sgRNAs, the complex binds to promoters or enhancer regions to upregulate endogenous gene expression. Common CRISPRa systems include the VPR multi-activator fusion and multi-component amplification systems such as SunTag or SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator). CRISPRa is used to study gain-of-function phenotypes, signal pathway activation, and mechanisms related to drug resistance.

In summary, CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa provide complementary approaches to perturb gene function via loss-of-function, expression repression, or gain-of-function, respectively. Together, they enable systematic functional interrogation of the genome across diverse research needs. A typical CRISPR screening workflow includes sgRNA library design and construction, viral packaging and cell delivery, application of defined selection pressures, high-throughput sequencing-based data analysis, and identification and validation of key gene targets.

Screening Strategies and Mode Comparison

CRISPR library screening offers high experimental design flexibility, allowing researchers to adopt different screening strategies and technical combinations based on study objectives, model systems, and expected phenotypes. The key dimensions of screening design include the following:

1. Screening Type: Positive vs. Negative Selection

Positive selection refers to screening conditions in which only cells carrying specific gene perturbations gain a survival or proliferation advantage, leading to their progressive enrichment in the population. This strategy is commonly used to identify genes that confer resistance or adaptive phenotypes, such as drug-resistance genes.

Negative selection focuses on sgRNAs that are gradually depleted during the screen, reflecting gene perturbations that limit cell growth or induce cell death. This approach is typically used to identify genes essential for cell survival, proliferation, or specific biological processes, or to discover potential targets that sensitize cells to therapeutic interventions. These two selection types differ in research objectives and data analysis methods, and the choice should be guided by the specific experimental context.

2. Screening System: In Vitro vs. In Vivo

In vitro screens are conducted in cultured cell systems, offering high throughput and controlled experimental conditions, making them suitable for early-stage large-scale target discovery and functional pre-screening. However, in vitro systems may simplify aspects of the cellular microenvironment.

In vivo screens, performed in animal models, allow the assessment of gene function in the context of tissue architecture, microenvironment, and multicellular interactions, providing a more physiologically relevant evaluation of gene function. Compared to in vitro approaches, in vivo screening involves greater experimental complexity, longer timelines, and higher resource requirements, and is typically applied during follow-up validation of candidate targets.

3. Choice of Perturbation Mode: CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa

The type of gene perturbation selected can substantially impact screening results and interpretation. CRISPR-KO induces complete gene loss, suitable for studying non-essential genes or assessing loss-of-function effects. CRISPRi achieves reversible transcriptional repression, ideal for essential or dosage-sensitive genes. CRISPRa enables upregulation of endogenous gene expression, allowing the study of gain-of-function phenotypes. Selection of the appropriate perturbation mode—or a combination of modes—should consider the target gene's expression profile, biological characteristics, and the scientific question under investigation.

4. Enrichment and Phenotypic Readout Strategies

Phenotypic readouts in CRISPR screening can be tailored to research goals. Common approaches include population-based screens that measure differences in cell survival or proliferation through changes in sgRNA abundance. Additional strategies involve fluorescence markers, surface proteins, or functional reporter systems, combined with cell sorting methods such as flow cytometry or magnetic bead separation to enrich specific subpopulations. With advances in imaging technology, high-content imaging is increasingly integrated into CRISPR screens to capture complex phenotypes, including cell morphology, subcellular structures, and dynamic processes.

Overall, CRISPR library screening enables systematic mapping of gene perturbations to phenotypic outcomes at the genome-wide scale, providing a robust framework for constructing gene-function networks. Different screening strategies and perturbation modes have distinct advantages, and careful consideration of study objectives, model systems, and technical feasibility during experimental design is essential to obtain biologically meaningful and reproducible results.

Technical Features, Advantages, and Challenges

As a genome-scale functional genomics approach, CRISPR library screening possesses multiple technical features that make it highly valuable for target discovery and mechanistic studies.

1. Efficiency and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

The CRISPR/Cas system enables stable and precise perturbation of target loci, facilitating the detection and quantification of cellular phenotypic changes. This capability allows for reproducible readouts in pooled cell populations, improving the reliability of high-throughput screening experiments.

2. Flexibility in Experimental Design

The availability of multiple perturbation modalities—CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa—allows targeted loss-of-function, transcriptional repression, or activation of genes. Combined with diverse selection pressures and model systems, these modalities support the construction of customized screening strategies tailored to a wide range of research questions.

3. Coverage and Systematic Capability

CRISPR library screening can be scaled to whole-genome coverage or focused functional gene sets and can additionally target regulatory regions such as promoters or enhancers. This enables systematic functional interrogation and target discovery under minimal prior assumptions, facilitating unbiased mapping of gene-function relationships.

Technical Challenges

Despite these advantages, CRISPR library screening faces several technical challenges:

1. Target Specificity and Off-Target Effects

Although CRISPR exhibits high targeting precision, large-scale library screens remain sensitive to sgRNA design quality, target locus selection, and genomic context. Potential off-target effects must be considered during experimental design and mitigated through multiple sgRNA validation and follow-up experiments.

2. Library Construction and Quality Control

Whole-genome sgRNA libraries require extensive sequence design, synthesis, and cloning steps. Ensuring high coverage, uniform representation, and library stability imposes strict requirements on technical platforms and experimental expertise.

3. Data Analysis and Interpretation

CRISPR screens generate large-scale sequencing datasets that necessitate robust bioinformatics workflows. Proper assessment of sequencing depth, batch effects, and statistical significance is essential to reliably identify functionally relevant candidate genes.

4. Limitations of Phenotypic Readouts

Conventional screens typically rely on cell survival, proliferation, or sortable markers as readouts. Complex phenotypes relevant to disease—such as morphological changes, subcellular structure remodeling, or dynamic cellular processes—may not be captured efficiently in pooled screening formats, highlighting a need for complementary high-content or single-cell readouts.

Overall, CRISPR library screening provides a high-throughput, systematic approach for large-scale functional genomics and target discovery. Its successful implementation depends on careful experimental design, robust technical platforms, and rigorous data analysis workflows, often combined with subsequent validation experiments and complementary technologies to ensure the reliability and biological relevance of findings.

Example Applications of CRISPR Library Screening

With the continuous maturation of CRISPR screening platforms and analytical methodologies, CRISPR library screening has been widely applied across diverse biomedical research contexts, particularly in functional genomics and drug discovery.

1. Cancer Target Discovery

In oncology research, CRISPR library screening is commonly used to systematically identify genes essential for tumor cell growth, survival, and adaptive responses. Genome-wide CRISPR-KO screens in cancer cell models can reveal candidate genes that significantly impact tumor phenotypes under specific genetic backgrounds or drug treatment conditions. For example, in BRAF V600E-mutant melanoma cell lines, introduction of the genome-wide GeCKO library followed by positive selection under BRAF inhibitor Vemurafenib treatment identified candidate genes whose knockout conferred drug resistance, such as NF1, MED12, and CUL3. These findings provide experimental evidence for dissecting molecular mechanisms underlying therapeutic resistance.

2. Drug Resistance and Mechanism of Action Studies

CRISPR library screening is broadly employed to study mechanisms of drug resistance and sensitivity. By analyzing the enrichment or depletion of specific sgRNAs in treated cell populations, researchers can infer the functional roles of genes in mediating drug responses. Moreover, CRISPRa-based screening strategies allow the investigation of how gene overexpression affects drug responsiveness, enabling mechanistic insights into drug action pathways and potential regulatory nodes.

3. Synthetic Lethality Screening

Synthetic lethality screening represents a critical application of CRISPR technology in precision oncology. By designing dual-sgRNA libraries to simultaneously perturb two genes, researchers can systematically identify gene pairs whose concurrent loss impairs cell viability. For instance, studies have constructed libraries containing approximately 150,000 dual-sgRNA combinations targeting multiple known cancer-related genes, leading to the identification of numerous synthetic lethal interactions. These results provide valuable insights for developing targeted therapies tailored to specific genetic backgrounds in tumors.

4. Other Research Applications

Beyond oncology and drug discovery, CRISPR library screening has been applied to infection and immunity research, metabolic regulation, and signaling pathway functional studies. For example, in viral infection models, CRISPR screening can identify host factors critical for pathogen entry or replication. In studies of metabolic disorders, systematic perturbation can reveal key genes regulating metabolic pathways. Across diverse biological processes, CRISPR library screening provides a scalable, generalizable tool for functional dissection at genome-wide or pathway-specific scales.

Integration Trends in CRISPR Screening

To overcome the limitations of traditional screening in phenotypic capture and information depth, CRISPR library screening is increasingly integrated with cutting-edge technologies, enabling higher-dimensional functional analysis and target discovery. Key trends include:

1. Integration with Single-Cell Omics

Combining CRISPR screening with single-cell RNA sequencing technologies, such as Perturb-seq or CROP-seq, allows direct measurement of transcriptomic changes at the single-cell level following gene perturbation. This strategy enables simultaneous analysis of thousands to tens of thousands of gene perturbations within a single experiment and reveals cell-type- or state-specific functional heterogeneity. Such integration provides critical support for high-resolution phenotypic dissection within complex cell populations.

2. Multi-Omics Fusion Analysis

Following CRISPR screens, integrating additional omics layers—such as proteomics, metabolomics, or epigenomics—facilitates multi-level validation and mechanistic investigation of candidate genes. For example, proteomic profiling of positively selected cells can help construct gene function networks, while metabolomic analysis can reveal how perturbations affect key metabolic pathways. This multi-omics approach provides a systematic view linking gene perturbation to molecular function, enhancing the biological interpretability of screening results.

3. High-Content Phenotypic Screening

The incorporation of high-content imaging allows CRISPR screens to capture complex phenotypes that are difficult to quantify with conventional readouts, such as changes in cell morphology, subcellular structure remodeling, and dynamic cellular processes. For instance, the CRaft-ID platform combines CRISPR-Cas9 screening with microraft arrays and high-resolution confocal imaging to observe subcellular phenotypes, such as stress granule formation, at single-cell resolution, enabling high-throughput phenotypic quantification.

Through these technological integrations, CRISPR library screening is evolving from single-phenotype observations to multidimensional, systematic, and quantitative functional analysis. This approach provides richer datasets and research strategies for drug target discovery, mechanistic studies, and precision medicine applications.

Ubigene CRISPR Library Screening Platform

Ubigene leverages its proprietary CRISPR-iScreen™ platform to offer an end-to-end solution for CRISPR library screening, spanning library design and construction, screening experiments, sequencing, and data analysis. The platform covers the entire workflow, including library design, plasmid construction, viral packaging, cell transduction, functional screening, high-throughput sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis, providing systematic support for functional genomics research and drug target discovery.

Core Technologies and Platform Advantages:

1. High Coverage and Uniformity

The platform utilizes high-efficiency competent cells and standardized cell pool preparation procedures, ensuring library coverage exceeding 99% with high uniformity. This provides a reliable foundation for large-scale functional gene screening.

2. Customizable Multi-Mode Editing Libraries

CRISPR-iScreen™ supports CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa modalities, enabling tailored library design to meet diverse research needs, including gene knockout, transcriptional repression, and gene activation.

3. Extensive Ready-to-Use Resources

The platform offers over 40 pre-constructed library plasmids and more than 400 standardized cell pool products. These resources can be flexibly combined to design experiments, reducing technical barriers and accelerating research timelines.

4. Versatile Screening Modalities

Both in vitro and in vivo screening are supported. Various selective pressures can be applied according to experimental requirements, including drug treatment, passaging stress, viral infection, and flow cytometry-based sorting, providing high flexibility for phenotype-based screens.

5. Integrated Data Analysis and Result Output

The interactive iScreenAnlys™ platform provides a user-friendly interface for visualization and analysis, delivering publication-quality results. It supports rapid interpretation of sequencing data and identification of candidate targets.

CRISPR-iScreen™ platform integrates library construction, cellular operations, screening assays, and high-throughput sequencing and analysis into a unified technical system. This integration reduces experimental complexity and operational difficulty while significantly shortening research timelines. The platform has been successfully applied in drug target discovery, functional genomics studies, and mechanistic validation, offering scalable, practical solutions for academic institutions and industry.

Industry Development Trends

The application of CRISPR library screening in global drug discovery is experiencing rapid growth. Numerous studies have demonstrated that this technology has been employed by thousands of independent laboratories and R&D projects for functional genomics and target identification. Industry reports indicate that as CRISPR screening becomes increasingly widespread in both academia and industry, the efficiency of novel drug target discovery is steadily improving and gradually scaling up. In pharmaceutical R&D workflows, an increasing number of organizations are incorporating CRISPR library screens into early-stage target validation to support systematic candidate target identification and mechanistic studies. Key future trends include:

1. Application in In Vivo and Patient-Derived Models

The technology is expanding from in vitro cell-based systems to in vivo animal models and patient-derived cells, allowing screening results to better reflect the influence of complex physiological environments, immune system interactions, and tissue microenvironments on gene function.

2. AI and Big Data-Driven Library Optimization

Integration of artificial intelligence algorithms and large-scale data analysis enables optimization of sgRNA design, library construction, and screening strategies, enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of target identification while reducing experimental costs and failure risks.

3. Integration of CRISPR-Derived Technologies

CRISPR-derived technologies, including base editing and prime editing, are gradually being incorporated into screening pipelines, enabling non-knockout functional perturbations, precise gene regulation, and the discovery of novel druggable sites.

4. Deep Integration with Multi-Omics and Single-Cell Technologies

Combining CRISPR screening with single-cell omics, multi-omics, and high-content phenotypic analysis allows multi-layered, systematic interrogation of gene function. This integration provides comprehensive datasets to support complex disease modeling and precision drug development.

In summary, CRISPR library screening will continue to play a central role in drug target discovery, mechanistic studies, and new drug development. The deep integration of CRISPR screening with single-cell analysis, multi-omics, and intelligent computational approaches represents a key direction for the future development of this technology in the biopharmaceutical sector.

Reference

Modell AE, Lim D, Nguyen TM, Sreekanth V, Choudhary A. CRISPR-based therapeutics: current challenges and future applications. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022 Feb;43(2):151-161. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2021.10.012. Epub 2021 Dec 21. PMID: 34952739; PMCID: PMC9726229.