Art of Gene Perturbation: Selecting the Perfect CRISPR Library for Your Experiment

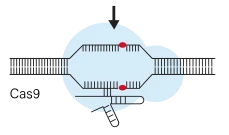

CRISPR screen enable powerful high-throughput loss- or gain-of-function studies. In these pooled formats, an entire genome (or sub-library) is targeted by many single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), each delivered by lentivirus to cells. CRISPR libraries fall into three main categories: CRISPR knock-out (CRISPRko) libraries, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) libraries, and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) libraries. CRISPRko uses an active Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks (DSBs) that generate frameshift mutations and permanent loss-of-function alleles.In contrast, both CRISPRi and CRISPRa use nuclease-deficient dCas9 fused to effector domains: dCas9-KRAB for transcriptional repression (CRISPRi) or dCas9 fused to activators (e.g. VP64-p65-HSF1 in the SAM system) for transcriptional activation (CRISPRa). These latter approaches modulate gene expression without cutting DNA, allowing reversible, tunable gene knockdown or upregulation. In practice, CRISPRko libraries are best when complete loss-of-function is desired, whereas CRISPRi is ideal for partial knockdown or studying essential genes, and CRISPRa is used to upregulate genes and discover gain-of-function phenotypes. Each modality has distinct strengths and limitations, which Ubigene analyze below.

Modality Definitions and Mechanisms

1.CRISPRko (Knockout): Uses wild-type SpCas9 (or another nuclease) guided by sgRNAs to cut target DNA. Repair by non-homologous end joining often yields indels causing frameshifts and truncated proteins.This typically produces complete gene knockout at the DNA level. Knockout is permanent and irreversible in each edited cell lineage, and is powerful for revealing gene loss-of-function phenotypes. However, multiple DSBs in a cell can cause toxicity or confound some hits (e.g. in copy-amplified regions).

2.CRISPRi (Interference): Uses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a repressor domain (usually KRAB) to sterically block transcription when targeted to a gene's promoter or early transcription start site (TSS). CRISPRi represses gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. It is reversible (effects persist only while dCas9-KRAB is present) and enables graded, tunable knockdown. Because it avoids DSBs, CRISPRi screens typically lack the cutting-related toxicity that CRISPRko can produce.However, CRISPRi knockdown often does not fully eliminate protein function, so very weak or partial phenotypes may be observed. It also requires careful TSS annotation to place guides correctly.

3.CRISPRa (Activation): Also uses dCas9 but fused to activation domains (e.g. VP64, p65, HSF1, SAM scaffold) to upregulate gene transcription when targeted upstream of a TSS.Like CRISPRi, CRISPRa is reversible and sequence-specific. CRISPRa screens reveal phenotypes caused by overexpression or gain-of-function. Compared to ORF overexpression libraries, CRISPRa uses endogenous regulation and often smaller library size (each gene only needs a few guides). One limitation is that not all genes can be strongly activated (e.g. if chromatin is inaccessible), and CRISPRa designs typically require complex constructs (activator fusions or SAM).

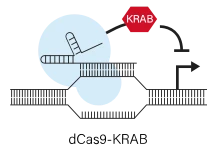

Based on its proprietary CRISPR-iScreen™ technology, Ubigene provides comprehensive, one-stop CRISPR screening services, including CRISPR-KO, CRISPRa, and CRISPRi customized libraries. The platform supports the entire experimental workflow — from high-throughput sgRNA library construction, viral packaging, and cell transduction, to drug selection, high-throughput sequencing, and bioinformatic data analysis.In addition to in vitro studies, Ubigene also offers in vivo CRISPR screening services to enable more physiologically relevant target discovery. Multiple delivery options are available to meet diverse research needs.

Pros and Cons of Each Library Type

Each library type has trade-offs for pooled screening:

1.CRISPRko advantages: Produces full gene knockout, yielding clear loss-of-function phenotypes. Well-established libraries exist (e.g. Brunello, TKOv3).High gene effect sizes facilitate discovery of essential genes. Works for most coding genes and even non-coding genes by deletion of regulatory elements. Screening robustness is high when multiple sgRNAs per gene are used.

2.CRISPRko disadvantages: Creates DNA cuts that can cause p53-mediated toxicity or cutting biases. In regions of high copy number, cutting across multiple alleles can confound results and cause false positives (spurious depletion).Knockouts may be lethal for essential genes, preventing recovery of hits. Also, any partial or haploinsufficient effects (where one functional allele already causes phenotype) cannot be distinguished.

3.CRISPRi advantages: Avoids DSBs, so no cutting toxicity or multi-locus effects.Can target essential genes, since repression can be partial (cell may survive with low expression). Suitable for non-coding RNAs or genes where DNA cutting is problematic. Reversible repression also allows more control (e.g. inducible knockdown). Since design is guided to promoters, CRISPRi can repress all transcripts of a gene simultaneously if targeted correctly.

4.CRISPRi disadvantages: Knockdown is usually incomplete - residual mRNA/protein may remain. Repression efficiency depends on TSS annotation and chromatin state. Some genes cannot be well-repressed (e.g. due to alternative promoters). Effect sizes may be smaller, requiring high screen sensitivity. Multi-guide requirement is as high as for KO to ensure robust hits.

5.CRISPRa advantages: Enables gain-of-function screening - finds genes whose overexpression affects the phenotype. Unlike cDNA/ORF libraries, CRISPRa uses the native promoter context and does not rely on a cDNA clone. It can activate all transcript isoforms in situ. Optimized CRISPRa libraries (e.g. Calabrese) have been shown to find known drug resistance genes and novel hits more effectively than older CRISPRa methods.

6.CRISPRa disadvantages: Not all genes can be activated to functional levels (some promoters may be refractory). CRISPRa library design is sensitive to exact TSS location and chromatin context. Generally requires more complex constructs (dCas9 plus activators or SAM), which can complicate screening logistics. Many sgRNAs (often ~10-15 per gene) are typically needed because of these challenges.

Choosing a CRISPR Library by Experimental Goal

The key to selecting a library is matching modality to the desired perturbation:

1.If you want gene knockouts or complete loss-of-function (e.g. for robust phenotypes like cell viability, essentiality, or detecting synthetic lethality in cancer cells), choose CRISPRko . This applies to typical negative-selection screens (dropout screens) for essential genes or positive-selection screens for drug resistance via loss of genes.

2.If you need to study essential genes or limit gene dosage, consider CRISPRi . For example, if knocking out a gene is lethal, CRISPRi can partially suppress it and reveal hypomorphic phenotypes. CRISPRi is also preferred if DNA breaks pose a risk (e.g. in primary or stem cells with fragile genomes).

3.If you want to upregulate or activate genes, use CRISPRa CRISPRa screens are ideal for discovering genes that drive drug resistance when overexpressed, or factors that increase cell growth or differentiation. For example, Calabrese (CRISPRa) outperformed SAM (another CRISPRa system) in identifying melanoma drug-resistance genes.

4.Sub-library or targeted screens: If you have a focused list of genes (pathway, family, or customized set), you can build a smaller library of CRISPRko/i/a guides accordingly. The principles below still apply, but you may tailor the number of guides per gene and coverage to this smaller scale.

Additional considerations:

1.Genomic context: For CRISPRko, avoid targeting multiple genomic sites (multi-copy genes) as DSBs may be problematic. For CRISPRi/a, ensure that promoter annotations are accurate (consider databases like FANTOM which use CAGE data for TSS).

2.Cell type and delivery: If delivery of multiple constructs (Cas9 vs dCas9-activator) is challenging, a two-component system may be needed (e.g. cells expressing Cas9 or dCas9 plus transduced sgRNA library). In practice, many labs use all three modalities in parallel to get a comprehensive view of gene function, since knockout, knockdown, and activation can yield complementary insights.

CRISPR Library Design: Key Parameters

Once a library type is chosen, careful design of sgRNAs and controls is crucial for success. Major factors include the number of guides per gene, coverage in the screen, target site selection, off-target control, and inclusion of proper controls.

1.Guides per Gene and Screening Coverage

Recommended guides per gene: Pooled libraries typically use 3-10 sgRNAs per gene This redundancy accounts for variable sgRNA efficiency, off-target risks, and statistical robustness.

- Libraries optimized with strong guide scoring have shown that even 3-4 guides per gene can achieve high performance.For example, the Brunello knockout library used 4 guides per gene and 1,000 non-targeting controls,while Dolcetto (CRISPRi) used 3 per gene. These designs were possible due to high on-target activity guides.

- However, if your genome annotation is incomplete or you include poorly characterized targets (e.g. lncRNAs), it's safer to include 6-10 guides per gene to ensure at least some efficacious ones.For very small libraries (e.g. focused subsets), adding extra guides can also mitigate the risk of false negatives from any single bad guide.

Coverage in screening: "Coverage" refers to the average number of cells (or reads) per sgRNA maintained throughout the experiment.

- Plasmid/library prep: When amplifying or packaging the library, ensure high representation. For sequencing validation of libraries, ~100-1000* read coverage per sgRNA is recommended.This means sequencing far more reads than sgRNAs to detect underrepresented guides before the screen.

- Cell culture: When infecting/transducing cells with the library, maintain ≥300-500* coverage per guide.For example, if a sub-library has 24,000 guides, transduce at least 60 million cells (500* coverage at MOI≈0.2).We generally aim for ≥500* at infection and maintain ≥300* in every selection passage. This helps prevent random dropout of guides. Low coverage (< 200*) dramatically increases stochastic loss and false negatives.

- Post-screen: Similarly, deep-sequence gDNA from harvested cells at >300-500* per guide.The Sigma-Aldrich guidelines note maintaining 300–500× at all stages (plasmid transduction, cell growth, final sequencing) for robust statistics.

In summary, more coverage and more guides per gene increase sensitivity and reproducibility, at the cost of larger culture/seq effort. When resources limit library size, one can compromise to ~3 guides and ~250-300* coverage, but values above 500* (for both plasmid and cells) are safer to minimize dropout.

2.sgRNA Target Site Selection

CRISPRko target sites: To maximize knockout efficiency and avoid escape isoforms, guides should target early coding exons. Empirically, targeting the first half (roughly the first 5-65% of coding sequence) yields many candidate sites with high impact.This avoids potential in-frame re-initiation at a downstream ATG or leaving most of the protein intact. In practice:

- Prefer sgRNAs in the 5'constitutive exons shared by all transcripts, so that all splice isoforms are disrupted.

- Follow a rule-of-thumb: avoid very first few codons (in case of alternative start sites) and avoid the extreme C-terminus. As Doench et al. advise, restricting sgRNAs to ~5-65% of the coding region still yields dozens of candidates for 1-kb genes.

- Use high on-target activity scores (like Rule Set 3, Azimuth) to prioritize the best within that region.

CRISPRi target sites: Guides must bind near the gene's transcription start site (TSS) to block transcription effectively.Based on genome-wide assays, an optimal window is roughly -50 to +300 bp relative to the annotated TSS (with the strongest effect often within ~100 bp downstream).Within this range, placing sgRNAs immediately downstream of the TSS intercepts RNA polymerase at initiation. Accurate TSS mapping (e.g. FANTOM CAGE data) is critical.

CRISPRa target sites: Guides for activation should bind upstream of the TSS to recruit transcriptional activators. Practical studies find the best region is around -400 to -50 bp upstream. This window ensures the activator domains (VP64, etc.) sit at promoters/enhancers to drive transcription. In CRISPRa library design (e.g. Calabrese), guides are chosen from this upstream window.For either CRISPRi or CRISPRa, design tools typically select guides within these promoter-proximal windows, accounting for PAM availability.

3.Off-Target Considerations

Minimizing off-target cutting or binding is essential for clean screens:

- Scoring and filtering: Use computational specificity scores (such as the MIT specificity score or CFD score) to estimate off-target risk for each sgRNA. High scores indicate likely unique targeting. Many design tools (e.g. CRISPOR) compute an overall specificity score (0-100 scale) reflecting off-target potential.In general, exclude guides with poor specificity (e.g. MIT score <50 or predicted to have many high-probability off-targets). Setting a threshold (like cutting frequency score >0.05 or similar) can weed out risky guides.

- Redundancy: Include multiple independent guides per gene so that any off-target effect from one guide is unlikely to give a false hit. As Doench notes, in screens one should require that multiple distinct guides for the same gene score before calling that gene a hit.This practice greatly reduces false positives from off-target activity because it is improbable that two different sgRNAs share the same spurious off-target.

- Screen analysis: Some pipelines explicitly model off-target possibilities (e.g. CRISPRcleanR) or allow removing guides that behave like off-target noise. Regardless, the best practice is careful design plus requiring concordance of multiple sgRNAs.

4.Control Guides

Proper controls are indispensable for interpreting enrichment/depletion:

- Non-targeting controls (NTCs): Include a set of sgRNAs with no genomic target (often called non-targeting or scramble guides) to measure background noise. These guides should have no perfect match in the genome (typically 20 bp random sequences with no off-targets). Recommended numbers are on the order of 1-5% of the library or at least 500-1000 NTCs.For example, the Brunello library (77,441 guides) included 1000 NTCs (~1.3%). A sizable NTC set is needed to robustly define the null distribution when calculating hit significance (p-values, FDR).These controls reveal any toxicity from Cas9 expression or virus, and set the baseline for fold-change calculations.

- Positive biological controls: Incorporate sgRNAs targeting well-known essential genes (e.g. ribosomal proteins, RNA polymerase subunits, DNA replication factors). In a cell proliferation screen, these sgRNAs should rapidly deplete, confirming that the screen captured expected essential gene dropouts.Observing robust loss of these controls signals that the screen worked. For example, in a CAR-T cell fitness screen, guides to core essential genes (POLR2L, PSMB4, RPL8) indeed showed strong depletion.

- Negative biological controls: Use sgRNAs against genes with no expected phenotype as additional baselines. A common choice is olfactory receptor (OR) genes, which are typically not expressed or functional in most cultured cells. In the CAR-T cell study, OR gene guides (“non-essential olfactory receptors”) had flat, neutral fold-changes similar to NTCs.These controls reassure that non-hits behave as expected. Other “safe harbor” loci or housekeeping genes known to have no effect in your assay can serve similarly.

- Internal replicates and safe harbors: Some screens also spike in guides to "safe" genomic sites (like AAVS1 or ROSA26) or use molecular barcodes (UMIs) to create pseudo-replicates, helping to normalize technical variation. While not strictly part of library design, these strategies improve data quality in large screens.

Including both NTCs and biological controls lets you validate that (1) selection worked (positive controls drop out) and (2) overall noise is low (negative controls stable). This is crucial for reliable hit-calling.

Ubigene could help the client design CRISPR library plasmids, including sgRNA design, chip-based synthesis, vector construction, plasmid electroporation and amplification, and NGS quality control.

Examples from Published Screens

Real-world screens illustrate the contrasts between KO, i, and a libraries:

- CRISPRko vs. CRISPRi: In a benchmark study by Doench's group, the optimized Brunello (CRISPRko) and Dolcetto (CRISPRi) libraries showed similar power to separate essential from non-essential genes. Both achieved comparable depletion of core essential genes when run under the same conditions. However, differences emerged: Brunello (Cas9 KO) showed a clear cutting effect (non-targeting guides dropped out due to DSB toxicity), whereas Dolcetto (CRISPRi) showed virtually no such effect.Thus CRISPRi avoided false positives caused by multi-locus cutting, an advantage in some contexts.This suggests that well-designed CRISPRi can match knockout for gene discovery, with the bonus of lower DNA damage artifacts.

- CRISPRi vs. CRISPRko: In another benchmark, screening in cancer cell lines with sets of top guides demonstrated that even a 3-guide-per-gene CRISPRko library could perform on par with larger libraries.Likewise, Dolcetto (3 guides per gene) outperformed older 10-guide CRISPRi libraries in essential gene screens.These studies highlight that guide quality (and design heuristics) can matter more than sheer quantity, allowing smaller libraries to achieve high efficiency.

- CRISPRa vs. other methods: Doench's Calabrese CRISPRa library was compared to both the SAM CRISPRa system and an ORF overexpression library in melanoma drug-resistance screens.

- Calabrese (CRISPRa) identified more significant resistance genes than SAM at stringent p-value cutoffs.For instance, at p<10^-4, Calabrese recovered 17-27 hits (depending on effector) versus far fewer in SAM. Both CRISPRa methods hit the known EGFR gene, but Calabrese found additional novel hits (e.g. P2RY8, LPAR5) not detected by SAM.Importantly, a held-out ORF screen (separate data) was also compared: across several cell types, Calabrese had a higher AUC for detecting “STOP” (growth-inhibitory) and “GO” (growth-promoting) genes than the ORF library, and significantly outperformed the older hCRISPRa-v2 library.In short, optimized CRISPRa libraries can exceed both older CRISPRa designs and traditional ORF libraries in activating genes and uncovering phenotypes.

These examples show that well-designed libraries across modalities can achieve powerful screens. Choice of KO/i/a will tilt the outcome (e.g. KO may be best for cytotoxic phenotypes, i/a for subtle or regulatory phenotypes), but in benchmark head-to-head comparisons the improved libraries often converge in ability to identify known essentials (for KO/i) or expected activators (for a).

Conclusion

In summary, choosing CRISPRko, CRISPRi, or CRISPRa depends on your biological question. Use CRISPRko for complete loss-of-function screens, CRISPRi when you need repression (especially for essential genes or when avoiding DNA cuts), and CRISPRa for gain-of-function/activation studies. The design of your library - number of guides, target site selection, coverage, and controls - is as important as modality. Following best practices (3-10 guides/gene, >300-500* coverage, TSS-targeted guides for i/a, early-exon guides for KO, filtering by specificity) ensures robust screening results.

Each approach has pros and cons, and often using multiple modalities yields the most insight. The latest libraries (Brunello, Dolcetto, Calabrese, TKOv3, etc.) have been rigorously optimized and should be used as templates or references.Finally, always include ample non-targeting and biological controls (essential and neutral genes) to validate your screen’s performance.With careful design, CRISPR screens can be a reliable tool for dissecting gene function at scale.

Ubigene provides end-to-end CRISPR screening services for both in vitro and in vivo applications. Our platform enables flexible configuration of diverse experimental conditions, including compound treatment, passaging, viral infection, and flow cytometry–based selection. We also offer multiple enrichment strategies, empowering researchers to DIY their own functional screening systems. This highly adaptable platform is built to meet the evolving needs of cutting-edge life science research. Furthermore,Ubigene developed iScreenAnlys™ CRISPR Library Analysis System, which is an interactive, in-house developed analysis platform featuring an intuitive, user-friendly interface that requires no coding experience. The platform supports multiple statistical methods and a wide range of customizable data visualizations, enabling personalized analysis workflows. Users can generate publication-ready figures and reports, accelerating data interpretation and scientific discovery.

Contact us to learn more>>FAQ

1.Q: How many sgRNAs per gene do I really need?

A: Generally 3–5 guides suffice if annotation is very good and your guides are highly scored.For less well-characterized targets or safety margin, use 6–10 guides. This redundancy combats variable sgRNA efficacy and off-targets.

2.Q: What coverage should I maintain?

A: Aim for ≥500× coverage at library prep and ≥300× during cell culture.This means infecting and expanding enough cells so each sgRNA is present in hundreds of cells. Lower than ~200× risks random dropout and lost hits.

3.Q: Where in the gene should guides target?

3.A: For knockouts, target early coding exons (first ~50–65% of the coding sequence) to maximize frameshift effects.For CRISPRi, target within ~−50 to +300 bp of the TSS (best ~+1 to +100 bp).For CRISPRa, target ~−400 to −50 bp upstream of the TSS.

4.Q: How do I control for off-target effects?

4.A: Use design tools to score specificity (MIT/CFD) and exclude low-scoring guides. Include multiple guides per gene and require that at least two guides for a gene give consistent phenotypes.This redundancy ensures an on-target effect. Also include proper NTCs and biological controls to identify spurious signals.

5.Q: What controls are essential?

A: Always include a sizable set of non-targeting control guides (e.g. 1–5% of library) that match no genomic site.Also spike in guides against known essential genes (positive controls) and neutral genes (negative controls, e.g. olfactory receptors). Essential-gene guides should deplete in dropout screens, and neutral-gene guides should behave like NTCs.This lets you verify screen performance and calibrate hit statistics.