CRISPR-StAR Enables High-Resolution In Vivo Library Screening

Breakthrough: CRISPR-StAR Enables High-Resolution In Vivo Library Screening

For a long time, conducting large-scale, high-resolution genetic screens in complex in vivo models such as mice has remained a formidable challenge. Traditional in vivo CRISPR screening approaches have been limited by low delivery efficiency, insufficient cellular representation, and an inability to resolve subtle phenotypic differences. These issues are particularly pronounced in oncology, where tumor cell heterogeneity, differential proliferative advantages, and the complexity of the tumor microenvironment make it difficult to obtain stable and reproducible screening results.

In December 2024, Ulrich Elling and his team at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences reported a groundbreaking technological advance in Nature Biotechnology — CRISPR-StAR (CRISPR–Stochastic Activation by Recombination).This method couples single-sgRNA expression cassettes with unique barcodes that can undergo CreERT2-induced stochastic recombination, thereby generating internal controls within the same clonal population after tumor establishment. This design maximizes consistency across experimental conditions and minimizes noise arising from cellular heterogeneity and bottleneck effects.CRISPR-StAR opens new avenues for functional genomics and biomedical research in complex in vivo contexts, marking a major step forward for CRISPR screening technologies toward high-resolution, low-noise genetic interrogation in living systems.

I.Research Background

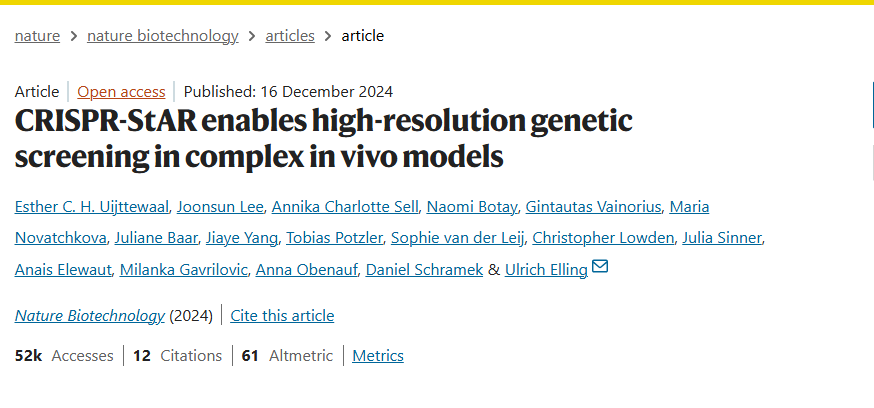

In traditional CRISPR library screening, it is essential to maintain a minimum of 500× coverage to achieve statistically reliable results. However, in in vivo tumorigenesis experiments in mice, the post-transplantation survival rate of cells is extremely low — only a small fraction of injected cells successfully survive and form tumors. For example, in this study, after injecting approximately 1 million cells, only 4,800–20,500 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) — each corresponding to a single vector — were detected across tumors derived from different cell lines. This drastic reduction in cell numbers results in the stochastic “loss” of many sgRNAs, introducing substantial randomness into the data and making it difficult to identify truly functional genes.

Moreover, distinct cellular clones display markedly variable proliferative capacities in vivo. Certain clones expand rapidly due to advantages conferred by the tumor microenvironment — such as preferential access to nutrients or oxygen — whereas others proliferate slowly or become completely quiescent. As reported in this study, nearly 50% of the total tumor mass was contributed by fewer than 4% of cell clones, indicating an extremely biased growth pattern. This intrinsic heterogeneity introduces significant noise, obscuring genuine gene effects.

Consequently, data noise represents an unavoidable limitation in in vivo CRISPR screening. Even under optimal conditions, the phenotypic effects of gene knockout are typically modest, with traditional screening approaches detecting enrichment or depletion signals of only around 20-fold. In contrast, in vivo variability can span several thousand-fold, vastly exceeding the magnitude of true screening signals. This overwhelming noise prevents stable discrimination between essential and non-essential genes and can result in numerous false-positive and false-negative findings.

II.Technological Innovation: CRISPR-StAR Breaks Through the Bottleneck of In Vivo Screening

The core innovation of CRISPR-StAR lies in its stochastic activation mechanism for sgRNAs (Fig. 1d).

Specifically, upon tamoxifen induction, CreERT2 recombinase mediates one of two irreversible recombination events:

● Deletion of an inhibitory element, leading to sgRNA activation; or

● Deletion of the tracrRNA sequence, resulting in an inactive state.

Through this stochastic recombination design, CRISPR-StAR establishes internal controls within the same cellular clone, thereby elegantly eliminating confounding influences from both extrinsic factors (e.g., oxygen availability, nutrient supply, immune pressure) and intrinsic cellular heterogeneity. As a result, the system markedly enhances the accuracy and reproducibility of screening outcomes.

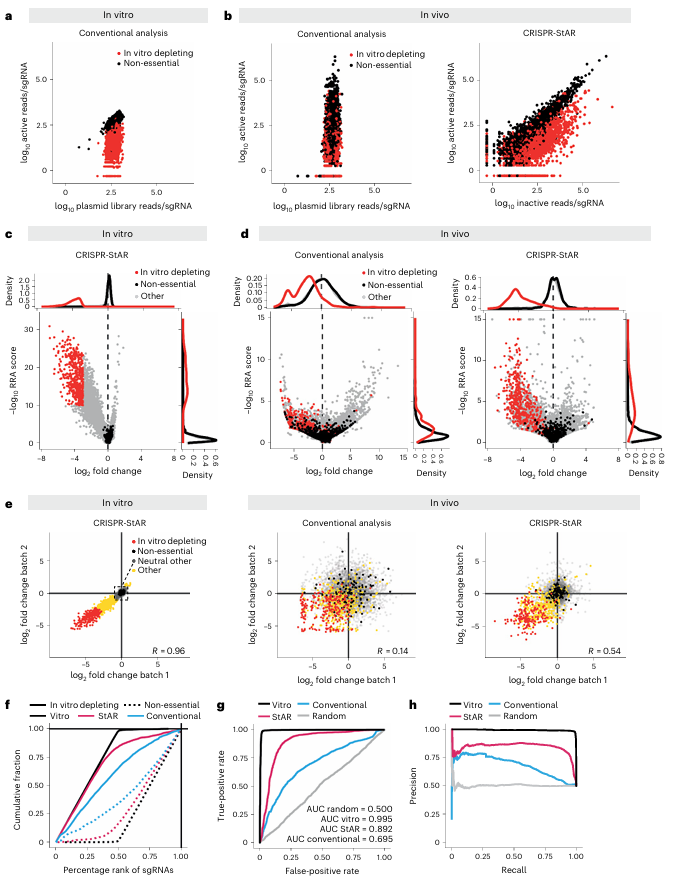

Experimental data demonstrate that, even under low coverage conditions (e.g., four cells per sgRNA), CRISPR-StAR maintains a high level of consistency, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.68, in stark contrast to the 0.07 observed with conventional methods under identical conditions (Fig. 1e–f). More importantly, CRISPR-StAR enables the precise discrimination between essential and non-essential genes within highly heterogeneous in vivo tumor models, substantially reducing both false-positive and false-negative results.

Figure 1. CRISPR-StAR overcomes high noise in experimental screening

III.Performance Validation: In Vitro and In Vivo Screening with CRISPR-StAR

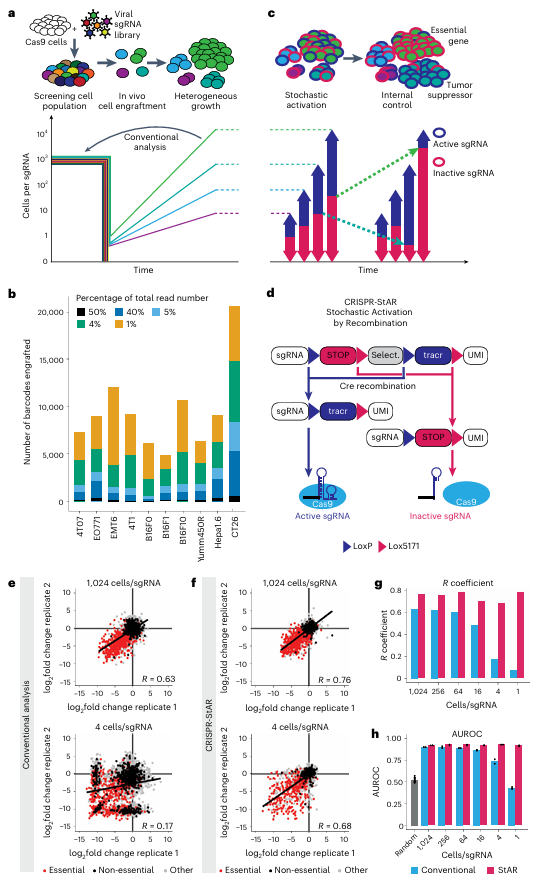

To ensure that CRISPR-StAR maintains a stable activation ratio across different cell lines, species, and genomic integration sites, the authors employed an optimized StAR-4GN vector. This improved construct achieved a final ratio of approximately 55% active sgRNAs to 45% inactive sgRNAs under in vitro conditions (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Optimization strategy of CRISPR-StAR for in vivo application

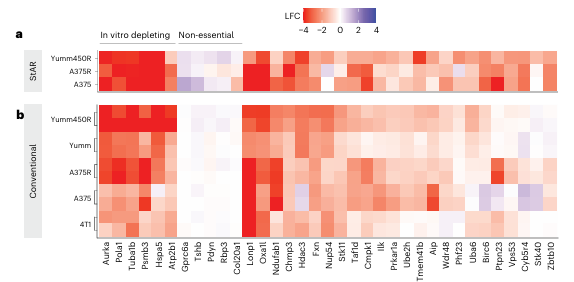

Due to the inherently low engraftment rate and substantial growth heterogeneity observed in vivo, the researchers employed Yumm1.7 450R murine melanoma cells to construct genome-wide CRISPR-StAR screening libraries both in vitro and in vivo. Compared with conventional library screening approaches, the unique internal control design of CRISPR-StAR effectively distinguished essential from non-essential genes even in the in vitro model (Fig. 3a, c).

When applied to the in vivo model, CRISPR-StAR demonstrated markedly superior performance. The method achieved clearer separation between targeted depleted genes and controls (Fig. 3d) with higher statistical significance compared to traditional analyses. Consistent with earlier findings (Fig. 1e–f), this enhanced resolution was primarily driven by a substantial reduction in data noise, rather than by failure to capture the depletion of essential genes.

Another key advantage of CRISPR-StAR is its ability to overcome batch effects through the use of internal controls. When comparing overlapping gene hits from two independent experiments conducted two years apart, traditional CRISPR screening yielded a correlation coefficient of only 0.17, indicating poor reproducibility. In contrast, CRISPR-StAR maintained a high correlation of 0.68 under the same conditions, demonstrating strong noise resistance and reproducibility (Fig. 3e).Furthermore, ROC curve and AUROC analyses confirmed that CRISPR-StAR significantly outperformed conventional screening methods in accurately identifying both gene enrichment and depletion events (Fig. 3f–h).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that—unlike traditional approaches—CRISPR-StAR allows activation of sgRNA expression only after tumor establishment, thereby eliminating confounding effects arising from cell transplantation and early-stage survival differences.

Figure 3. Comparative performance of conventional analysis and CRISPR-StAR screening

IV.Technical Advantages: CRISPR-StAR Reveals In Vivo–Specific Genetic Hits

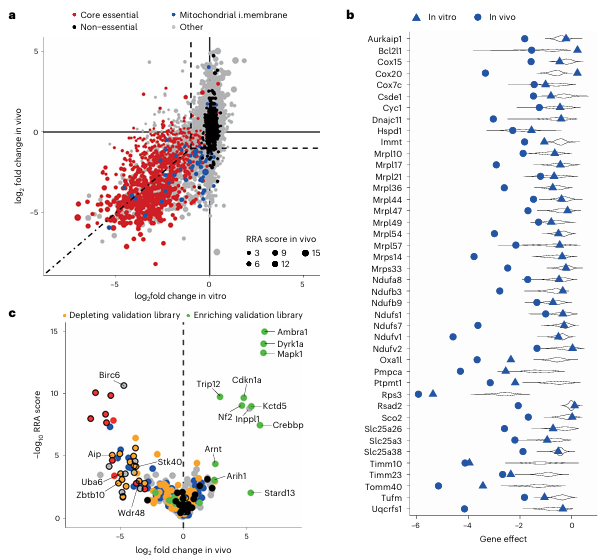

Using a genome-wide CRISPR-StAR library, the researchers successfully uncovered a critical role of mitochondrial function in sustaining tumor cell survival within a BRAF inhibitor–resistant murine melanoma model. Unlike conventional in vitro screening, melanoma cells in in vivo conditions exhibited a strong dependence on the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathway (Fig. 4a, b).

This finding indicates that tumor cells in the in vivo microenvironment cannot rely solely on glycolysis for energy production; instead, they require efficient mitochondrial metabolism to support rapid proliferation. In contrast, traditional in vitro screening often fails to identify such genes due to differences in nutrient availability, underscoring the profound influence of the in vivo microenvironment on tumor gene function.

Figure 4. In vivo–specific genetic hits identified in therapy-resistant melanoma

In addition, CRISPR-StAR identified several tumor suppressor genes with in vivo–specific effects, such as Stk40 and Zbtb10. Loss of these genes led to selective enrichment of tumor cells in vivo, and their effects were likewise observed in human tumor cell models, demonstrating pronounced in vivo specificity (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. In vivo–specific genetic hits identified in human and mouse models

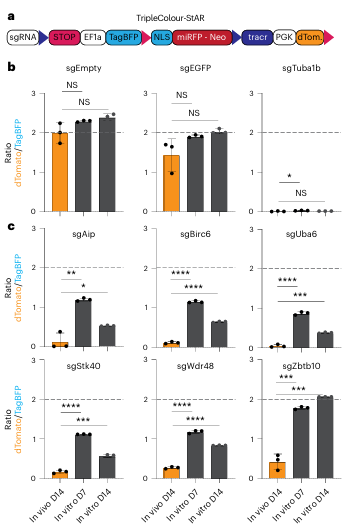

Finally, the researchers performed individual validation of the in vivo–specific hits identified by CRISPR-StAR. Considering the differences between constitutive and inducible sgRNAs as well as variability in tamoxifen-mediated recombination efficiency, they constructed a new vector capable of distinguishing non-recombined, recombination-activated, and recombination-inactivated sgRNA states.The results demonstrated that all in vivo–specific hit genes exhibited markedly stronger dependence in vivo than in vitro (Fig. 6c). Notably, Zbtb10 showed particularly strong context-dependent effects. Overall, these single-gene validations confirm that CRISPR-StAR is capable of identifying genes with strong in vivo–specific or context-dependent functional requirements.

Figure 6. Validation of individual in vivo–specific genetic hits

V.Significance and Applications

Although CRISPR-StAR relies on stable expression of Cas9 and CreERT2 and can be influenced by variability in tamoxifen induction in vivo, its development represents a revolutionary advance for precision medicine research. By combining high-resolution genetic screening with an internal control mechanism, CRISPR-StAR overcomes the longstanding bottlenecks of traditional CRISPR screens in complex in vivo disease models. Its high data reliability and resolution make it a powerful tool not only in cancer research but also in drug development and the precision treatment of other complex diseases.

Are you struggling with how to efficiently perform in vivo target gene screening?

Don’t worry — Ubigene now offers a comprehensive in vivo CRISPR library screening service.

Our platform faithfully recapitulates real disease contexts and provides access to multiple mouse models, allowing a customized in vivo screening strategy tailored to your research needs.

In addition, our service includes professional data interpretation support. Leveraging Ubigene’s proprietary iScreenAnlys™ CRISPR Library Analysis Platform, researchers can perform high-quality data analysis without any programming skills.

Whether your goal is to explore unknown disease mechanisms, identify potential drug targets, overcome tumor drug resistance, or optimize immunotherapy strategies, Ubigene provides a one-stop, high-quality solution for your research needs.

Contact us for more information>>

Reference

Uijttewaal ECH, Lee J, Sell AC, Botay N, Vainorius G, Novatchkova M, Baar J, Yang J, Potzler T, van der Leij S, Lowden C, Sinner J, Elewaut A, Gavrilovic M, Obenauf A, Schramek D, Elling U. CRISPR-StAR enables high-resolution genetic screening in complex in vivo models.

Nat Biotechnol. 2024 Dec 16. doi: 10.1038/s41587-024-02512-9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39681701.