Ubigene Empowers Overcoming Cancer Targeting “Bottlenecks”

Ubigene Empowers Overcoming Cancer Targeting “Bottlenecks” — Peptide Amphiphiles “Hitchhike” on Endogenous Lipoproteins for Precision Solid Tumor Imaging and Therapy

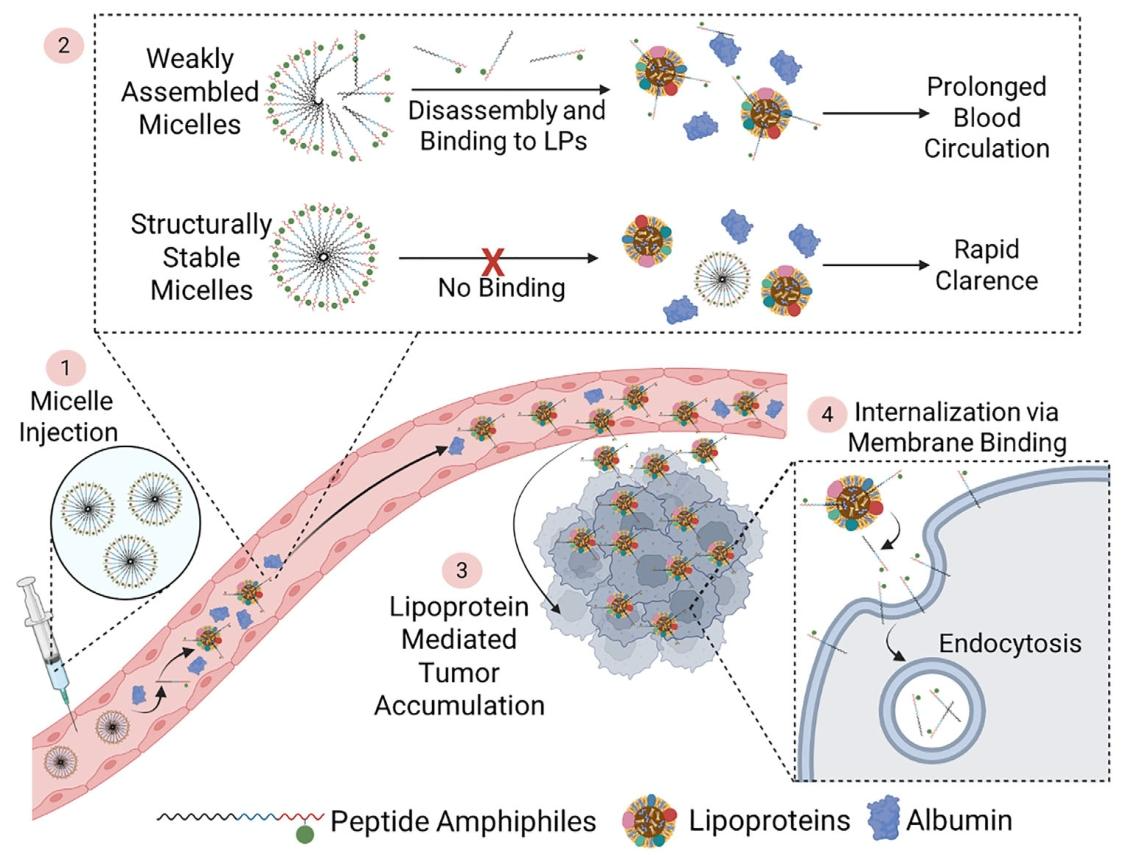

In cancer diagnostics and therapy, the in vivo interactions between nanomaterials and biomolecules directly determine their biological fate and critically influence therapeutic outcomes. In 2025, Li Xiang et al. published a study in Advanced Materials titled “Peptide Amphiphiles Hitchhike on Endogenous Biomolecules for Enhanced Cancer Imaging and Therapy”, demonstrating that self-assembling peptide amphiphile (PA) nanostructures can exploit dynamic interactions with endogenous biomolecules and leverage natural physiological processes to achieve targeted delivery to multiple solid tumors. For this study, key cell lines — LDLR Knockout cell line (HeLa) and Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line (HeLa) were provided by Ubigene, supplying essential tools for investigating the interaction between PAs and endogenous lipoproteins. The research revealed that, in circulation, these self-assembled PA nanostructures undergo disassembly and reassembly with lipoproteins, prolonging their blood circulation time and significantly enhancing tumor accumulation and retention.

Research Background

Peptide amphiphiles (PAs) can self-assemble into nanostructures in aqueous solutions through hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen bonding. They exhibit excellent biodegradability, biocompatibility, and low immunogenicity, making them highly promising for applications in drug delivery, molecular imaging, and tissue engineering.

However, current research in the field largely focuses on enhancing the structural stability of PA assemblies in biological environments to ensure their functional integrity in vivo, while neglecting their dynamic interactions with biological systems. Although the importance of nano–bio interactions for the in vivo fate of nanomaterials is well established—for instance, complement proteins adsorbed on nanoparticle surfaces can trigger rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system, whereas binding to albumin or apolipoprotein E can prolong circulation time and enable receptor-mediated uptake by cancer cells—such interactions remain poorly studied in self-assembling nanomaterials, including PA nanostructures.

In light of this, the present study investigates the interactions between PAs and endogenous biomolecules and cells, and their impact on tumor-targeting ability and biodistribution, aiming to provide both theoretical insights and experimental evidence for the development of more efficient cancer diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Research Highlights

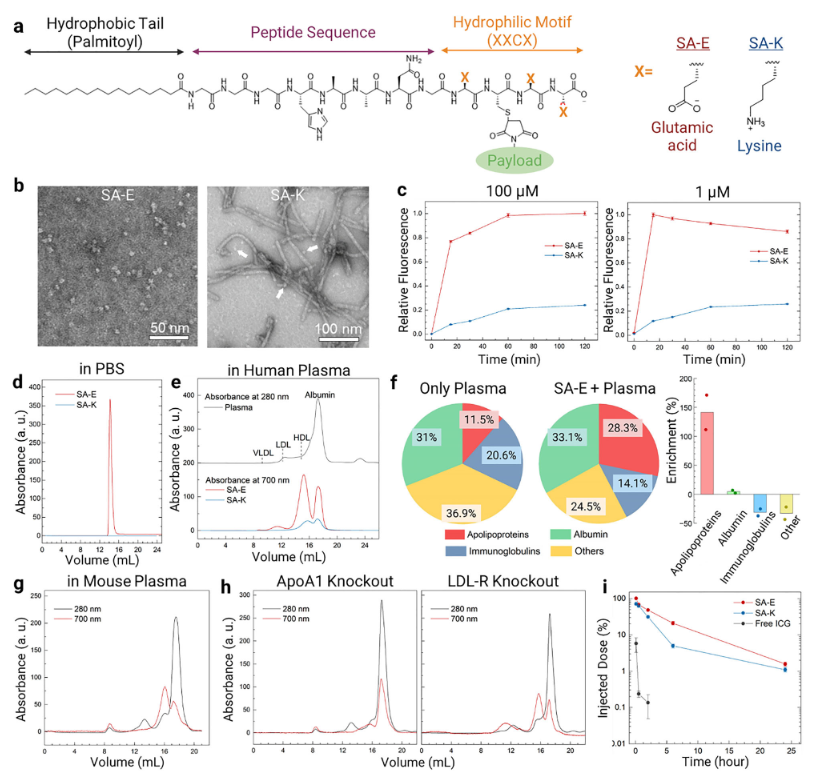

Significant Differences in the Plasma Stability of PA Nanostructures

The research team designed two peptide amphiphiles (PAs) with distinct hydrophilic segments — SA-E and SA-K (Self-Assembly Lysine). Both share a common self-assembly motif (GGGHAANG) with an N-terminal palmitoyl modification to promote assembly, while the hydrophilic portion contains three glutamic acids (E) for SA-E and three lysines (K) for SA-K. Both PAs were labeled with the near-infrared fluorescent dye ICG to track their in vivo behavior.

To examine how structural differences affect stability, the team used transmission electron microscopy (TEM). SA-E self-assembled into spherical micelles approximately 5–10 nm in diameter, whereas SA-K primarily formed rod-shaped micelles ~10 nm in diameter and several hundred nanometers in length, with only a few spherical micelles. Fluorescence assays in 10% human plasma showed that the ICG fluorescence intensity of SA-E increased approximately threefold faster than that of SA-K. Fluorescence anisotropy experiments revealed significantly higher anisotropy for SA-K than SA-E, indicating that SA-K micelles are more rigid and structurally stable.Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations further supported these observations: SA-E ultimately formed spherical aggregates, whereas SA-K largely retained its initial tubular structure. SA-K exhibited a greater number of intermolecular contacts and a lower root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), confirming stronger intermolecular interactions and enhanced structural stability relative to SA-E.

To further clarify the interactions of SA-E and SA-K with plasma components, fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) and mass spectrometry analyses were performed. SA-E rapidly disassembled in plasma and preferentially bound to lipoproteins, especially high-density lipoprotein (HDL), with a total binding ratio of 65.3% (HDL: 59.8%), while binding to albumin was 34.7%. In contrast, SA-K, due to its structural stability, exhibited significantly lower plasma binding, with a binding efficiency approximately 1/4.5 that of SA-E. Furthermore, the unlipidated control No-SA remained largely unbound in plasma (95.3% free), with only minor binding to albumin (4.2%) and HDL (0.5%).These results indicate that PAs preferentially associate with plasma lipoproteins, and the extent of this interaction is strongly influenced by nanostructural stability, with SA-E showing higher lipoprotein binding than SA-K.

Figure 1

PA–Lipoprotein Binding Prolongs Circulation Time and Enables Receptor-Independent Cellular Uptake

The research team investigated the in vivo behavior of SA-E in wild-type mice, ApoA1 knockout mice (with significantly reduced HDL levels), and LDL-R knockout mice. One hour after injection, in wild-type mice, 65.8% of SA-E was bound to lipoproteins (HDL: 55.2%), and 34.2% was bound to albumin, with 98.9% of the SA-E fluorescence signal remaining in plasma and minimal uptake by blood cells. In ApoA1 knockout mice, SA-E binding to HDL dropped to 16.7%, while binding to albumin increased to 75.4%. In LDL-R knockout mice, total lipoprotein binding slightly increased to 73%, with HDL still being the major component (44.4%).

Pharmacokinetic analyses showed that 6 hours after injection, 21% of SA-E remained in circulation, and the area under the blood concentration–time curve (AUC) was 2.1 times higher than SA-K, indicating a markedly prolonged circulation time. In contrast, only 5% of SA-K remained at 6 hours, and free ICG decreased to less than 1% within 30 minutes, becoming undetectable at 6 hours. No-SA persisted slightly longer than free ICG but retained only ~2.5% at 6 hours. These results confirm that PA–lipoprotein interactions are critical for extending systemic circulation.

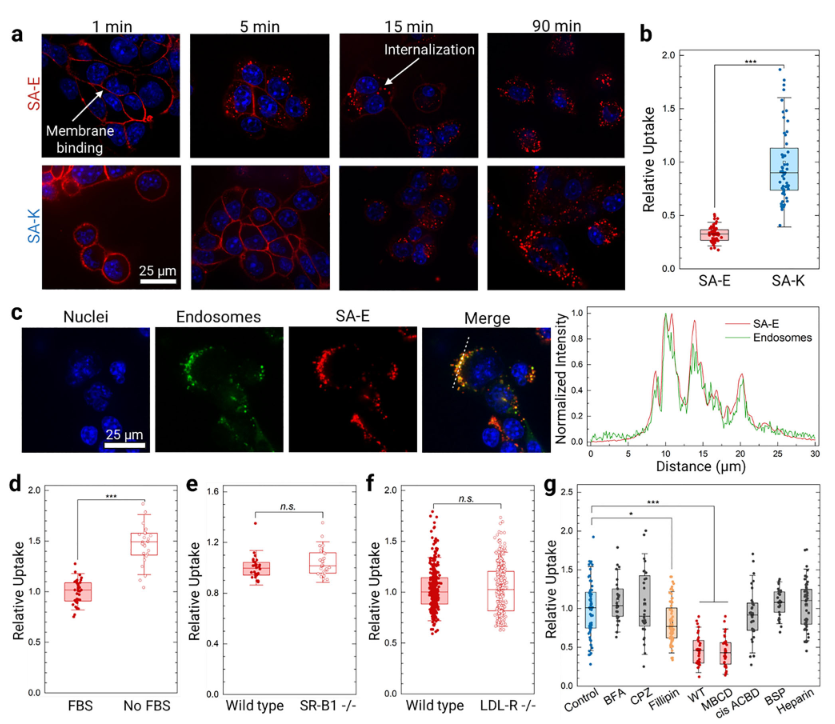

To evaluate cellular internalization, the team used Cy5-labeled PAs in vitro. Both SA-E and SA-K rapidly bound to the 4T1 mouse breast cancer cell membrane and were subsequently internalized. Due to its positive charge, SA-K uptake was approximately threefold higher than SA-E. Endosome staining revealed a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.605 ± 0.02 between SA-E and endosomal fluorescence, confirming endocytosis as the primary uptake pathway.

Further studies showed that in serum-free medium, SA-E uptake increased 1.6-fold, suggesting competitive binding between serum biomolecules and the cell membrane. In LDL-R knockout HeLa cells and SR-B1 knockout TRAMP-C2 cells, SA-E uptake remained unchanged, excluding dependence on these two lipoprotein receptors. Inhibitor studies demonstrated that wortmannin and methyl-β-cyclodextrin significantly reduced SA-E internalization, while filipin partially inhibited uptake. These results indicate that SA-E is internalized primarily via cholesterol-rich lipid raft domains of the cell membrane, independent of any specific surface receptor.

Figure 2

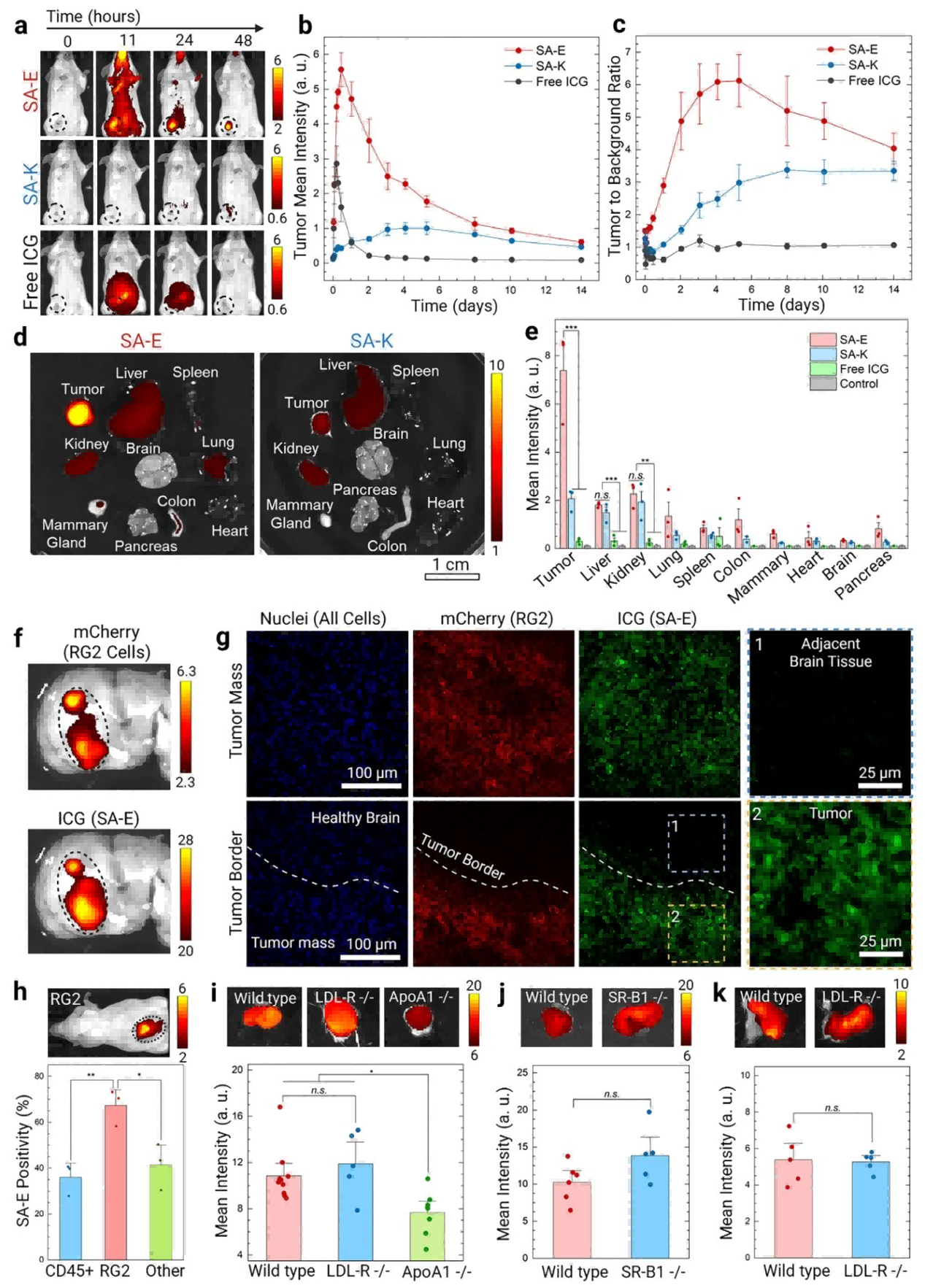

SA-E Achieves Broad-Spectrum Tumor Targeting with Dual Imaging and Therapeutic Potential

To further evaluate tumor accumulation and retention of SA-E and SA-K, the research team used the 4T1 breast cancer tumor-bearing mouse model. SA-E showed significantly higher tumor accumulation compared with SA-K and free ICG. Tumor fluorescence peaked 11 hours post-injection and remained detectable for up to 2 weeks, while background signals in normal tissues were largely cleared within 2 days. The tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) remained above 2.5, reaching a maximum of 5–6.

Biodistribution studies revealed that SA-E concentration in tumors (1.9% ± 0.4% ID/g tissue) was significantly higher than in the liver (0.8% ± 0.1% ID/g tissue) and other organs, yielding a tumor-to-liver signal ratio of 4.1, compared to only 1.4 for SA-K.In a rat RG2 glioblastoma model, the fluorescence signal of SA-E in tumors was 16-fold higher than in adjacent healthy brain tissue and fully overlapped with mCherry-labeled RG2 cancer cells. Confocal imaging confirmed that SA-E was evenly distributed throughout the tumor, clearly delineating tumor boundaries, with no uptake by healthy brain tissue.

Flow cytometry analysis showed that 70% of RG2 tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment internalized SA-E, whereas uptake by leukocytes and stromal cells was only 35–40%. These experiments demonstrate that SA-E efficiently accumulates in tumors and retains long-term localization, supporting its potential as a platform for both tumor imaging and therapeutic delivery.

Figure 3

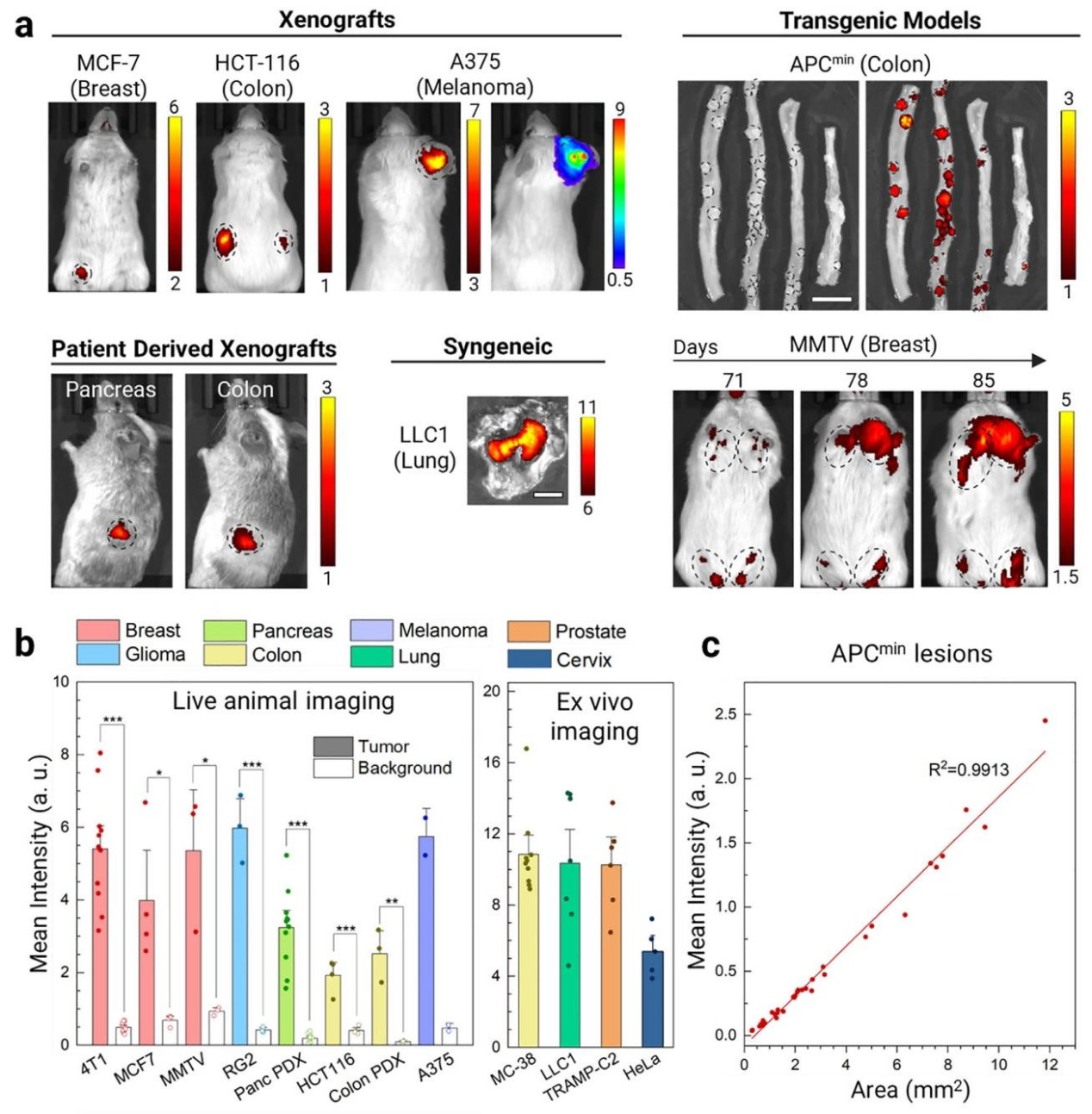

To evaluate the general tumor-targeting capability of SA-E, the research team tested 13 different tumor models, including xenografts, allografts, transgenic, and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), covering eight tissue origins: breast, colon, melanoma, lung, pancreas, cervix, prostate, and brain. SA-E exhibited highly specific tumor accumulation across all models.In the MMTV-PyMT transgenic breast cancer model, SA-E was able to detect early microlesions at 71 days of age and track tumor growth continuously until 85 days, when the tumors had enlarged. In the APC^min transgenic colorectal cancer model, SA-E enabled 100% detection of small intestinal adenomas (71/71) and colonic polyps (4/4). Tumor size showed a strong linear correlation with SA-E signal intensity (R = 0.9913), allowing identification of microlesions smaller than 1 mm².

These results demonstrate that SA-E possesses broad-spectrum and highly specific tumor-targeting capability, capable of detecting both early-stage and established tumors across diverse tissue types.

Figure 4

Building on the finding that SA-E binds to lipoproteins, selectively targets tumor cells, and accumulates for extended periods, the research team explored its potential as a highly efficient, low-toxicity chemotherapeutic delivery platform. The highly potent drug monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) was conjugated to SA-E via a cathepsin B-cleavable linker (vcMMAE), forming SA-E-MMAE.TEM imaging confirmed that SA-E-MMAE retained spherical micelle morphology, while fluorescence anisotropy and FPLC experiments demonstrated that it still disassembled in plasma and bound to HDL, indicating that structural stability was largely preserved.

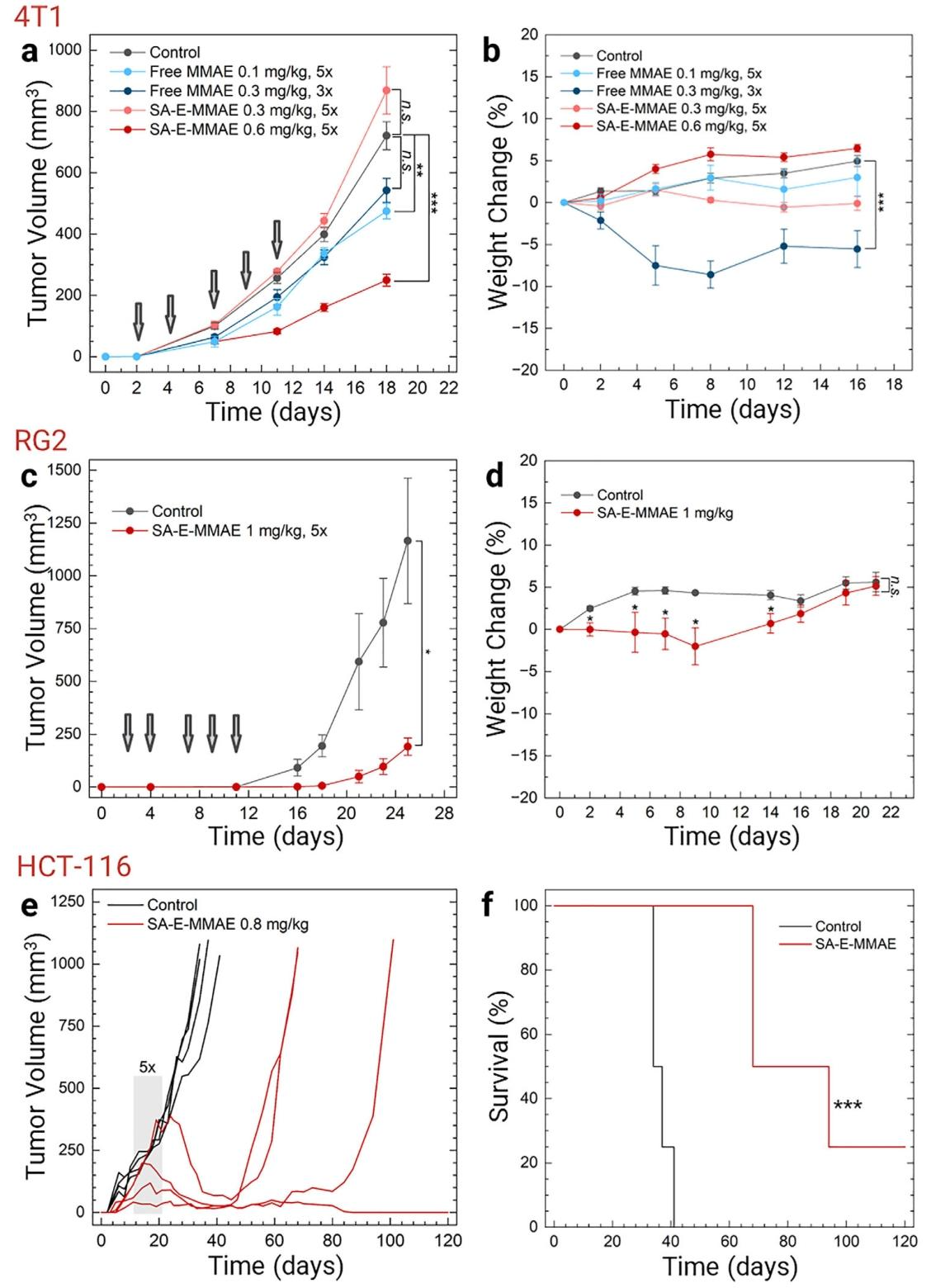

In the 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse model, SA-E-MMAE (0.6 mg/kg, 5 injections) inhibited tumor growth by 75% without significant weight loss. In contrast, free MMAE at 0.3 mg/kg was too toxic, and treatment had to be terminated after 3 injections.In the RG2 glioblastoma model, SA-E-MMAE (1 mg/kg, 5 injections) suppressed tumor growth by 80%. In the HCT-116 colorectal cancer model, SA-E-MMAE (0.8 mg/kg, 5 injections) reduced tumor volume from 150 mm³ to 40 mm³, and one mouse remained tumor-free for 120 days, significantly prolonging survival.

These results demonstrate that SA-E can serve as a robust platform for selective, long-circulating, and low-toxicity delivery of potent chemotherapeutics, achieving strong antitumor efficacy across multiple tumor types.

Figure 5

Summary

This study for the first time reveals that weakly assembled peptide amphiphiles (PAs) achieve broad-spectrum tumor targeting via a dynamic mechanism:

● Disassembly in circulation

● Reassembly with endogenous lipoproteins

● Prolonged systemic circulation

● Lipid-raft–mediated internalization in the tumor microenvironment

This mechanism overcomes the limitations of conventional nanomaterials, which typically rely on either structural stability or specific receptor-mediated uptake for targeting.The developed PA, SA-E, combines simple modular design, high biocompatibility, broad-spectrum tumor targeting, early imaging capability, and efficient low-toxicity drug delivery, providing a novel, versatile platform for precision cancer imaging and therapy.

Figure 6. Cellular internalization mechanism of PAs

Support Provided by Ubigene

The key cell lines used in this study — LDLR Knockout cell line(Hela) and Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line(Hela) were provided by Ubigene, enabling the discovery that SA-E internalizes primarily via cholesterol-rich lipid raft domains of the cell membrane, independent of specific surface receptors.

Ubigene Offers Customized KO Cell Line Services.With over 8,000 successful gene knockout cases, our proprietary technology can increase gene editing efficiency by 10–20×. All delivered KO clones are fully validated via Sanger sequencing and PCR. We also maintain a large inventory of 8,000+ ready-to-use KO cell lines. Take advantage of our promotional pricing starting at $990, with delivery in as fast as 1 week.

Don’t miss this opportunity—browse the Red Cotton OmniCell Bank to find the cells you need.

Contact us for more technical support>>

Reference

Xiang L, Stewart MR, Mooney K, Dai M, Drennan S, Holland S, Quentel A, Sabuncu S, Kingston BR, Dengos I, Bonic K, Goncalves F, Yi X, Ranganathan S, Branchaud BP, Muldoon LL, Barajas RF, Fischer JM, Yildirim A. Peptide Amphiphiles Hitchhike on Endogenous Biomolecules for Enhanced Cancer Imaging and Therapy.

bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 May 17:2024.02.21.580762. doi: 10.1101/2024.02.21.580762. Update in: Adv Mater. 2025 Oct 4:e09359. doi: 10.1002/adma.202509359. PMID: 40462899; PMCID: PMC12132515.