Decoding Gene Function in Living Systems: Advances in In Vivo CRISPR Library Screening

CRISPR pooled-library screens have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling genome-wide perturbation in a single experiment.Traditionally, most high-throughput genetic screens were conducted in vitro in cell culture. However, cells in a dish lack many features of living tissues: they do not fully recapitulate the complex cell-cell interactions, extracellular matrix, immune signals, blood supply, and tissue architecture of an organism. These missing in vivo signals can mask important phenotypes. For example, an engineered organoid or spheroid may mimic some 3D aspects, but still “fail to fully recapitulate the complexity of a living organism”. Direct in vivo CRISPR screens – perturbing genes in cells within a living animal – can reveal genetic dependencies and phenotypes that are unique to the tissue context. In fact, multiple studies have shown that in vivo screens identify cancer metastasis drivers or immune-modulatory genes that would be missed by in vitro screens conducted in parallel. By combining high-throughput CRISPR technology with animal models, researchers can bridge the gap between preclinical models and clinical biology.

- High throughput: in vivo CRISPR libraries can target tens of thousands of genes or regulatory elements simultaneously.

- Direct genotype-phenotype mapping: each sgRNA barcode is tracked by next-generation sequencing (NGS) before and after selection, directly linking genes to observed traits.

- High precision: CRISPR-Cas9 editing creates defined knockouts or mutations with minimal off-target effects

These features make CRISPR library screening vastly more efficient and unbiased than older perturbation methods. Compared to candidate-gene approaches, pooled CRISPR libraries allow systematic discovery of both known and novel regulators of a phenotype, without prior hypotheses.

Why Move From In Vitro to In Vivo Screens?

Traditional CRISPR screening strategies have largely evaluated gene function using in vitro and in vivo models as separate experimental systems. While in vitro screening is well suited for simple traits and rapid testing, its limitations become clear for complex biology. For example, drug resistance, immune evasion, tissue invasion, and metastatic spread involve interactions among multiple cell types and signals that only occur in the whole organism. Studies have repeatedly shown that tumor-microenvironment interactions and metastasis are best modeled in vivo. CRISPR in vivo screening recapitulates the native microenvironment and dynamic physiological conditions, enabling gene-function studies in the context of blood supply, extracellular matrix, immune cells, and organ architecture.

At the same time, in vivo screens carry unique challenges.They require efficient delivery of the CRISPR components to target cells in the animal, often through viral vectors. Common methods include lentiviral transduction, plasmid or transposon delivery, or adeno-associated virus (AAV) infection.For genome-scale libraries, achieving a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) and high coverage (many transduced cells per sgRNA) is harder in vivo than in a dish.The use of transgenic animals with a conditional Cas9 allele (e.g. LSL–Cas9 mice) can simplify delivery by eliminating the need to deliver the Cas9 gene itself.Even so, special strategies are often needed to target specific cell types (promoter selection, viral tropism, or cell sorting) and to pool cells from multiple animals to reach sufficient coverage.

Although tumor-derived exosomes are known to activate fibroblasts and participate in shaping the TME, most current research focuses on the roles of proteins and RNAs within exosomes. In contrast, significantly less attention has been given to how exosomal aberrant DNA influences TME homeostasis and contributes to tumor progression and metastatic spread. While the functional role of PIK3CA mutations within tumor cells has been largely elucidated, therapeutic strategies directly targeting PIK3CA mutations in cancer cells have shown limited efficacy in preventing colorectal cancer (CRC) metastasis.

Despite these hurdles, the value of in vivo screens is high. They allow researchers to study gene function during development, in disease progression, or under whole-animal physiology.For example, in vivo CRISPR screens can be applied to cancer metastasis models, immune cell function in immunotherapy, drug response in animal models, and even noncancer systems such as diabetes or neurobiology.By delivering perturbations directly to cells in their natural niche, in vivo screens capture three key features absent in indirect screens: intact extracellular environment, a functional immune system, and normal tissue signals.

Indirect vs. Direct In Vivo Screens

A systematic comparison between in vitro and in vivo CRISPR library screening highlights a fundamental trade-off between experimental scalability and physiological relevance, underscoring why many clinically relevant genetic dependencies emerge only under in vivo conditions.

Two general strategies have emerged for in vivo CRISPR screening. Indirect in vivo screens first deliver the CRISPR library in vitro (for instance by infecting cancer cells with a pooled lentivirus library) and then transplant those modified cells into animals.This approach avoids the challenge of delivering CRISPR reagents inside the animal. The classic example is the landmark metastasis screen by Zhang et al. (2015), who first transduced a mouse tumor cell line with a genome-wide library, then injected those cells into mice. After tumors formed, the researchers sequenced sgRNA barcodes in primary and metastatic lesions to identify genes that, when knocked out, drove metastasis.

Indirect screens have been widely used in cancer research, especially for metastasis and immunotherapy. For instance, in vivo screens using transplanted T cells have revealed regulators of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and immunotherapy response.Similarly, indirect screens in transplanted pancreatic beta cells have identified genes affecting autoimmune diabetes.The main limitation is that they generally require immunocompromised host animals (to allow engraftment of foreign cells) and may not fully recapitulate the native tumor microenvironment.

Direct in vivo screens, by contrast, deliver the CRISPR library into the host animal’s cells directly, without a transplantation step. For example, one can inject sgRNA-expressing lentivirus or AAV into a specific organ of a mouse, which is either wild-type (with Cas9 expressed via transgene) or transgenic for Cas9.This approach maintains fully intact tissue context and an immune system. Notably, direct screens have begun to be applied to solid organs like liver, lung, and brain, where localized delivery is possible.For instance, a small in vivo screen in mouse liver used plasmid transposons to introduce sgRNAs and Cas9 by hydrodynamic tail vein injection.Such direct methods are more complex to implement, but they avoid the xenograft bottleneck and can uncover regulatory interactions that require the native microenvironment.

Workflow: Experimental Protocol for In Vivo CRISPR Screening

A typical in vivo CRISPR screen follows these core steps(Just for your reference):

- Design and prepare the sgRNA library. A genome-scale or focused library of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) is designed to target thousands of genes (or noncoding regions) relevant to the study. For mouse models, libraries like GeCKO or Brie are commonly used.The oligo pool is cloned into a lentiviral or AAV vector.

- Generate Cas9-expressing cells or animals. If not using a transgenic Cas9 animal, the target cells (e.g. tumor cell line) are first engineered to stably express Cas9. For example, one can transduce cells with a Cas9-GFP lentivirus and select a polyclonal Cas9+ pool.

- Produce viral library and infect cells. The sgRNA plasmid library is packaged into viral particles. The target cells are infected at low MOI (typically ~0.3-0.5) so that each cell receives only one sgRNA, ensuring a clear genotype-phenotype link.Infection is done in replicate to achieve high coverage (e.g. 100-500 cells per sgRNA). Infected cells are then selected with antibiotics (e.g. puromycin) to enrich for transduced cells.

- Engraftment into animals. The pooled, CRISPR-modified cells are implanted into the appropriate mouse model. Common approaches include subcutaneous injection of a tumor cell pool, orthotopic (organ-specific) implantation, or intravenous injection for metastasis models. If studying drug resistance or host factors, compound treatment may begin at this stage.

- Phenotypic selection in vivo. Allow tumors or tissues to grow under physiological conditions. Depending on the goal, researchers may wait for primary tumor formation, metastatic colonization, drug response, or other readouts. At endpoint (typically weeks after injection), animals are sacrificed and tissues of interest (e.g. primary tumor, metastatic organs, bone marrow, etc.) are collected.

- Sequencing and data analysis. Genomic DNA is extracted from collected cells and tissues. The sgRNA barcode region is PCR-amplified and analyzed by NGS. By comparing the abundance of each sgRNA in the harvested tissue versus its abundance in the initial cell pool, one can identify which sgRNAs (hence genes) were depleted or enriched during in vivo growth.

Each of these steps is designed to maintain the connection between a gene knockout and the in vivo phenotype. Care is taken to use adequate cell numbers and multiple mice to cover the library and to include control arms (for example, wild-type cells or cells with non-targeting sgRNAs). Rigorous statistical analysis (e.g. MAGeCK or other algorithms) is then used to rank candidate “hits” whose loss-of-function strongly affects tumor growth, metastasis, survival, or other phenotypes.

Data Analysis: Interpreting In Vivo Screen Results

After sequencing, data interpretation follows general pooled-screen principles. Briefly, sgRNAs that become under-represented in tumors or metastases (relative to the initial library) indicate that the targeted gene is essential for that stage of growth.Conversely, sgRNAs that are over-represented suggest that gene loss promotes growth or metastasis.In the lung-metastasis screen example, the researchers looked for sgRNAs that dropped out in primary tumors or metastases (essential genes) and sgRNAs that expanded (negative regulators).Enriched sgRNAs (in tumors) might point to tumor suppressors whose knockout gave the cell a growth advantage, whereas depleted sgRNAs might reveal oncogenes or survival factors required for tumor expansion.

Statistical thresholds are applied to identify significant hits across biological replicates. For instance, in one case 935 sgRNAs (targeting 909 genes) were significantly enriched in mouse primary tumors,many of which were linked to apoptosis and suggest key roles in growth. Hits are typically validated by secondary assays: researchers will individually knock out a candidate gene in cells and re-test tumor/metastasis potential to confirm the screening result.This two-stage process (pooled screen followed by targeted validation) ensures that the findings are reproducible and biologically meaningful.

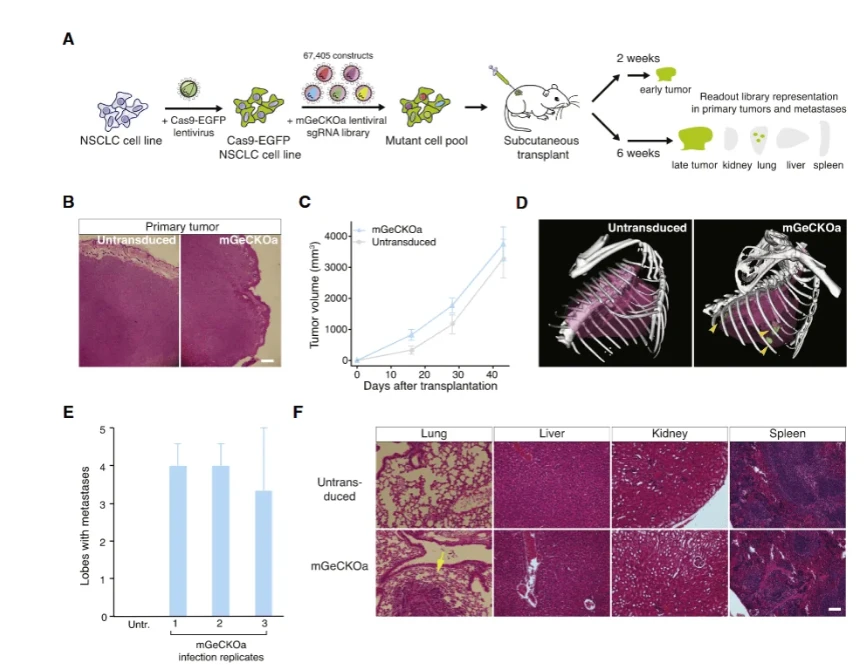

Figure 1. Tumor growth and metastasis following injection of a genome-wide CRISPR knockout library into mice. In this example screen (from Zhang et al., 2015), a Cas9-expressing lung cancer cell pool carrying a mouse GeCKO knockout library was injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Primary tumors (left) grew in both library and control groups. Remarkably, lung metastases (bottom right) appeared only in the mice harboring the CRISPR library cells, indicating that loss of certain genes can drive metastatic spread.

Applications of In Vivo CRISPR Screens

In vivo CRISPR screens have already been applied to a range of biological questions. Cancer metastasis is one of the earliest and most impactful applications. In the seminal Cell paper by Zhang et al. (2015), a mouse lung cancer cell pool with a genome-wide knockout library was used to identify metastasis suppressor genes.By harvesting and sequencing lung lesions, the study found that loss-of-function mutations in certain genes (e.g. NF2, PTEN, CDKN2A) greatly increased metastasis.They then confirmed these hits by knocking them out singly, which indeed accelerated metastasis formation in mice.Clinically, many of these candidate genes are also downregulated in metastatic tumors from patients, suggesting the mouse screen had translational relevance.

Similarly, in vivo CRISPR screens have begun to illuminate tumor-immune interactions. For example, a recent screen in an orthotopic mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer identified the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 as a key regulator of how tumors interact with macrophages and respond to checkpoint therapy.In that study, a custom sgRNA library targeting ~4,500 genes was introduced into TNBC cells, which were then injected into syngeneic mice. Tumor sequencing and iterated screening uncovered COP1 as a gene whose loss synergized with immunotherapy. This highlights how in vivo screens can be tailored to therapy context: mice were treated with checkpoint inhibitors during the experiment, enabling the discovery of genes affecting drug response.

Beyond cancer, in vivo screening is exploring other fields. T-cell biology is one area: pooled screens in murine or human T cells have been used to find factors that control T-cell infiltration into tumors or differentiation states.Likewise, neuroscience researchers have proposed using viral CRISPR libraries to probe gene function in brain circuits, and stem cell screens in animals could reveal developmental regulators. Even metabolic disease has seen in vivo perturbation: a screen of pancreatic β-cells transplanted into a diabetic mouse model uncovered genes that protect against autoimmune attack.

Common to all these applications is the need to maintain animal health and use appropriate controls. Screens involving pathogenic infections or drug treatments can uncover host factors as well as direct targets. For example, in infectious disease, one could screen for host genes that allow virus replication or for bacterial genes needed to colonize a host. The flexibility of CRISPR libraries (knockout, CRISPRi/CRISPRa, or base editing libraries) means that in vivo screens can probe loss-of-function, gain-of-function, or precise mutation effects on physiology.

In Vivo Screening Protocol Highlights

The practical execution of in vivo CRISPR screens has some variations but follows the workflow above. Some key protocol considerations include:

- Coverage and Replicates: Ensure the infected cell pool maintains high representation of all sgRNAs (e.g. ≥100x coverage).In practice this means infecting tens to hundreds of millions of cells across replicate flasks and using multiple mice.

- Multiplicity of Infection (MOI): Keep MOI low (<0.5) so that each cell typically carries a single sgRNA, simplifying downstream analysis.

- Selection Pressure: Depending on the phenotype, consider using both positive and negative selection strategies. For tumor screens, most readouts are “negative selection” (dropout of essential gene sgRNAs). In drug screens, one might look for sgRNAs that become enriched only under treatment.

- Control Arms: Always include a baseline control sample (e.g. cells before injection) and control mice if possible. Non-targeting or “safe” sgRNAs in the library help normalize counts.

- Endpoint Analysis: Choose tissue collection carefully. For metastasis, one collects both primary tumors and metastatic organs (lungs, liver, etc.).For drug studies, compare treated vs untreated groups.

- Sequencing Depth: vSequence each sample deeply enough to quantify the majority of sgRNAs. Commercial screening services (and open tools like iScreenAnlys™) now exist to streamline data processing, including quality control, MAGeCK statistics, and pathway analysis.

Case Study: Mouse Tumor Metastasis Screen

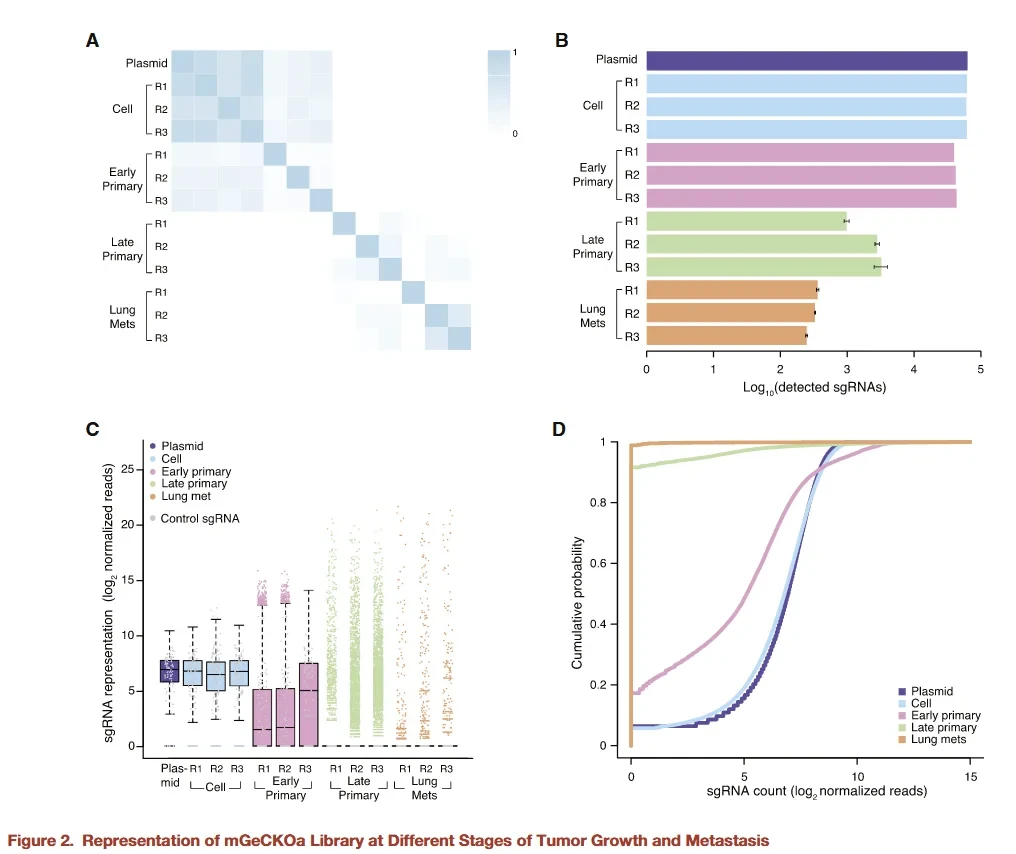

A clear example of in vivo CRISPR screening is provided by Zhang et al. (2015) in Cell, as summarized by Ubigene's application note.In that study, a non-small cell lung cancer cell line (Kras^G12D^; p53^-/-^; Dicer1^+/-^) was engineered to stably express Cas9.A genome-wide sgRNA library (67,405 guides) was used to infect these cells (MOI ~0.4, 400* coverage) and select for transduction.The pooled cells were then injected subcutaneously into nude mice. After 6 weeks, primary tumors and lung metastases were harvested.Deep sequencing of sgRNAs revealed which knockouts had become depleted or enriched during tumor growth and metastasis.

Representative results (Figure 1) showed that lung metastases formed robustly only in the mice carrying the CRISPR library pool, not in controls. Analysis of sgRNA abundance identified hundreds of candidate genes: 935 sgRNAs (909 genes) were significantly enriched in primary tumors,many involved in apoptosis or cell survival. In metastatic lung lesions, 147 sgRNAs (105 genes) were enriched, including known tumor suppressors Nf2, Pten, Cdkn2a and novel hits like Trim72, Fga, miR-345, miR-152. Importantly, some sgRNAs were much more abundant in metastases than in the primary tumor, pinpointing genes specifically required for the metastatic step.These discoveries were validated by making individual knockouts of several top hits and showing that each knockout accelerated lung metastasis in new mice.

Figure 2. Analysis of sgRNA enrichment in a mouse tumor metastasis screen. Pooled sequencing of tumors and metastases identifies which guide RNAs were depleted or enriched. In this example, hundreds of guides targeting genes related to apoptosis were enriched in tumors, highlighting their roles in cancer progression.Enriched guides in lung metastases (not shown) pointed to regulators like Pten and Cdkn2a that specifically suppress metastatic colonization.

Other Applications and Insights

Beyond metastasis, in vivo CRISPR screening is uncovering new biology across fields. In tumor metabolism, for example, one study using an inducible “stochastic activation” CRISPR library (CRISPR-StAR) found that melanoma cells grown in vivo (but not in vitro) required mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.This highlights how nutrient constraints in the tumor microenvironment create unique genetic vulnerabilities that only appear in vivo. Likewise, in infectious disease or immunology, screens can identify host factors that modulate pathogen replication or immune evasion.

The challenges of in vivo screening also drive innovation. One major issue is clonal heterogeneity and bottlenecks: only a small fraction of injected cells may engraft and expand in the mouse, leading to stochastic loss of many sgRNAs.Advanced designs like CRISPR-StAR introduce internal controls to reduce noise.Nevertheless, even conventional approaches can succeed by using very high initial coverage and multiple replicates to mitigate dropout effects. Data analysis must account for the higher variance typically seen in vivo (often thousands-fold fluctuations) compared to in vitro.

As technology advances, new readouts promise to extend in vivo screening. Single-cell RNA-seq or lineage tracing can be coupled to CRISPR perturbations in tissues, revealing not just which genes are selected for, but also how they rewire cellular programs. Advances in AAV engineering and inducible Cas9 strains are expanding the range of targetable cell types. Ultimately, in vivo CRISPR screening is becoming an essential bridge between high-throughput genomics and organismal biology.

Summary

Taken together, integrating insights from in vitro and in vivo CRISPR screening provides a more comprehensive understanding of gene function, bridging reductionist cell-based assays with organism-level biology, disease progression, and therapeutic response. By transplanting or delivering pooled CRISPR libraries into animal models, researchers can identify genes that drive complex phenotypes like tumor growth, metastasis, drug response, and immune interactions.The workflow—from sgRNA library design and viral infection to animal engraftment and deep sequencing—builds on standard CRISPR screening methods but adapts them to the in vivo setting.Compared to in vitro screens, in vivo screening offers unmatched physiological relevance at the cost of greater experimental complexity. Nevertheless, recent studies demonstrate the feasibility and high value of in vivo screens. For example, a landmark genome-wide in vivo screen in mice systematically uncovered novel metastasis suppressors,and follow-up small libraries and validation confirmed these targets.Other in vivo screens have already identified actionable targets in cancer immunotherapy and beyond.

In summary, in vivo CRISPR library screening combines the throughput of pooled CRISPR knockout with the full complexity of animal models, enabling unbiased discovery of gene–phenotype links in health and disease.As genomic technologies and analysis tools improve, in vivo screens will continue to open new frontiers in functional genomics, bridging the gap between cell culture studies and real-world biology.

Ubigene provides fully integrated, end-to-end CRISPR in vivo screening services.

ith a rigorous pre-experimental optimization system and a robust quality management framework, Ubigene delivers seamless, one-stop in vivo CRISPR library screening—from library design and viral packaging to animal studies, sequencing, and data interpretation. Every stage of the workflow is tightly coordinated to ensure high reliability, reproducibility, and screening depth. In addition, Ubigene has developed the iScreenAnlys™ CRISPR Library Analysis Platform, an intelligent, zero-code solution for CRISPR screen data analysis. Simply upload your sequencing files, and the platform automatically executes quality control, MAGeCK-based statistical analysis, and pathway enrichment. iScreenAnlys™ outputs ranked target heatmaps, differential gene volcano plots, and other publication-ready visualizations, delivering immediate insights for downstream research and manuscript preparation.

Contact us to get more information >>>Reference

Chen S, Sanjana NE, Zheng K, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell. 2015;160(6):1246-1260. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.038